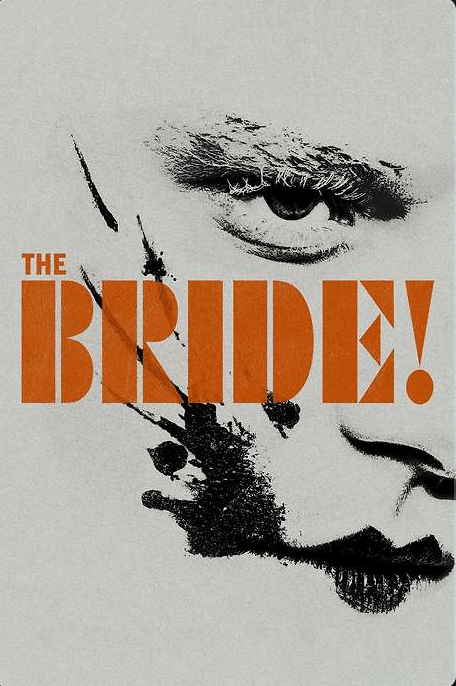

There’s a good movie somewhere inside The Bride!—perhaps several.

There’s a good movie somewhere inside The Bride!—perhaps several. The irony is that the film itself feels as Frankensteined together as the titular creation at its center. Maggie Gyllenhaal’s ambitious reinterpretation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and James Whale’s immortal Bride of Frankenstein (1935) clearly springs from a place of imaginative vision. The problem is not the ideas. The problem is that too many of them are stitched together without the narrative cohesion necessary to bring the creature fully to life. What emerges is a fascinating but uneven cinematic experiment: a film whose strongest parts often struggle against the whole.

In 1930s Chicago, groundbreaking scientist Dr. Euphronious (Annette Bening) brings a murdered young woman Ida (Jessie Buckley) back to life to be a companion for Frankenstein’s monster (Christian Bale). What happens next is beyond what either of them could ever have imagined.

There is little doubt that Gyllenhaal set out to craft an imaginative and thought-provoking reexamination of Frankenstein mythology. The ambition is evident in nearly every frame. Yet the screenplay and editing lack the discipline required to shape that ambition into something structurally coherent. In an ironic parallel to Frankenstein’s own creation, the film is assembled from intriguing narrative parts—each compelling in isolation—but collectively they never quite form a unified organism. Any one of those narrative threads might have served as a more stable foundation than the combination presented here.

It is possible that The Bride! may one day find a second life as a cult curiosity. Cinema history is filled with examples of films—The Rocky Horror Picture Show and even Showgirls—that were initially met with confusion before later audiences embraced their eccentricities. But both of those films possessed an essential ingredient that this one struggles to sustain: entertainment. Each of them understood its own satirical target and leaned confidently into the theatricality of its premise. The Bride! gestures toward satire but never fully commits to it. The result is a tonal tug-of-war between melodrama and camp. Had the film embraced the latter more confidently, the experience might have been far more exhilarating. Intentional camp signals to the audience that the filmmakers are in on the joke; here, the film often takes its own eccentricities too seriously.

Narratively, the film wanders. Yet the performative dimension proves far sturdier. Jessie Buckley and Christian Bale share a compelling chemistry that anchors the film whenever the plot threatens to drift. Annette Bening brings welcome gravitas to her doctor, while Penélope Cruz’s detective—though played with conviction—is underserved by a character that ultimately has too little to do. Indeed, the performances are what keep the audience invested when the narrative itself begins to lose its footing.

Visually, however, Gyllenhaal demonstrates undeniable directorial confidence. Her eye for composition yields moments of striking cinematic beauty. The cinematography and production design elegantly bridge old and new interpretations of the mad scientist mythos. Laboratories glow with stylized menace while the broader world of the film evokes both classical Hollywood romanticism and contemporary visual flair. Particularly during the musical interludes, lighting and camera movement become expressive tools rather than mere ornamentation.

One of the film’s most charming creative flourishes lies in its affectionate nods to classic romantic melodramas and golden-age song-and-dance spectacles. Busby Berkeley’s Footlight Parade, Gold Diggers of 1933, and other Warner Bros. musical traditions echo throughout the film, not merely as nostalgic references but as narrative devices that illuminate the emotional worlds of the characters. The moments when Frank (Bale), Ida (Buckley), and the camera operator drift into choreographed reverie feel as though they have stepped directly off a 1930s soundstage. In these sequences, the film’s imagination briefly achieves the synthesis the rest of the narrative seeks.

Yet structurally the film remains overburdened. Elements of Romeo and Juliet, Bonnie and Clyde, and The Bride of Frankenstein all compete for narrative dominance, while the shadow of Mary Shelley herself looms as an interpretive framework. Any one of these inspirations could have produced a compelling through-line with traces of the others woven in. Instead, the film attempts to juggle all of them simultaneously. The result is a narrative compass that spins without settling on a clear direction.

This imbalance points toward a broader issue increasingly visible in contemporary cinema: the challenge of the writer-director auteur. Gyllenhaal clearly possesses a strong visual sensibility and a director’s instinct for atmosphere and composition. But here the screenplay does not display the same level of discipline as the filmmaking. The modern industry often encourages directors to function simultaneously as writers and producers, yet history demonstrates that some of the greatest films emerge from collaboration rather than singular authorship. There are exceptional writer-directors—but they remain the exception rather than the rule. In this case, Gyllenhaal’s imaginative vision might have benefited enormously from the partnership of a dedicated screenwriter capable of translating those ideas into a tighter narrative structure.

None of this diminishes the ambition behind The Bride!. The film is imaginative, visually striking, and intermittently electrifying. It simply struggles to unify its many inspirations into a cohesive whole. With a stronger narrative foundation, Gyllenhaal’s directorial instincts might have produced something truly extraordinary.

Instead, we are left with a fascinating creature assembled from promising parts—alive, perhaps, but never quite fully formed. And like Frankenstein’s creation itself, the result inspires equal parts admiration and frustration.

Ryan is the general manager for 90.7 WKGC Public Media and host of the show ReelTalk “where you can join the cinematic conversations frame by frame each week.” Additionally, he is the author of the upcoming film studies book titled Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror. After teaching film studies for over eight years at the University of Tampa, he transitioned from the classroom to public media. He is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Follow him on Twitter: RLTerry1 and LetterBoxd: RLTerry