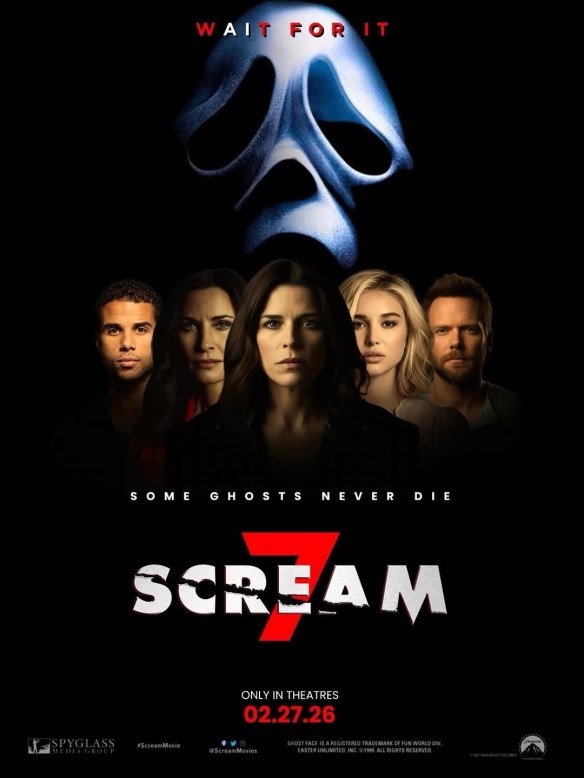

There is a difference between resurrecting a franchise and reviving its pulse. Scream 7 understands that distinction.

There is a difference between resurrecting a franchise and reviving its pulse. Scream 7 understands that distinction. This seventh installment aligns far more closely with Scream 2–4—with the 1996 original remaining peerless—than with the tonal divergence of entries five and six. It is not an attempt to eclipse the original nor to extend the reboot-era mythology. Instead, it is a recalibration: a deliberate return to the structural mechanics and tonal balance that once defined the series—brutal yet playful, self-aware yet grounded, meta without collapsing into parody. It restores the rudimentary whodunit spine, re-centers the franchise’s emotional trinity, and reasserts consequence in a narrative space that had begun to flirt with immunity. It may not reinvent the mask, but it remembers how to make it frightening—and fun—again.

The premise is straightforward: a new Ghostface emerges in the quiet Indiana town where Sidney Prescott has built a life beyond trauma. When her daughter becomes the next target, Sidney is pulled back into the cycle she has spent decades surviving. The simplicity is intentional. This is not a mythology-expanding installment. It is a structural restoration.

When I wrote about the original Scream in 2020, I emphasized how Wes Craven and Kevin Williamson fused satire and sincerity—how the film functioned simultaneously as genre critique and legitimately tense mystery. And in reflecting on Scream 4, I argued that the franchise’s survival depended on maintaining that balance between irony and genuine stakes. Scream 7 understands that lineage. It does not reinvent the formula; it reasserts it.

The humor is sharper than in the previous two entries, and the dialogue once again flirts with meta-awareness without dissolving into self-congratulation. More importantly, the whodunit framework returns to prominence. Scream has always been more mystery than massacre—a slasher disguised as a parlor game. Here, suspicion lingers. Motives matter. The audience is invited to participate again rather than merely observe. That interactive quality—so essential to the original—has been restored.

The kills are similarly recalibrated. They are decisive, occasionally shocking, and refreshingly unwilling to protect characters based on audience expectation. Supporting players are bloodied. Familiar faces are not insulated by nostalgia. The film reinstates a fundamental rule: no one is safe. In doing so, it restores tension that had softened in recent installments.

At the center of this recalibration is the reaffirmation of the franchise’s trinity: Sidney Prescott, Gale Weathers, and a classically-derived Ghostface presence that evokes the psychological intimacy of earlier entries. Strip Scream to its essentials and it has always revolved around those pillars. When they are foregrounded, the franchise regains coherence.

If Scream 4 was the franchise’s first major recalibration, Scream 7 feels like its long-delayed mirror. The fourth installment ushered Scream into the digital revolution—interrogating self-made celebrity, the commodification of trauma, and the toxic symbiosis between violence and visibility. It marked the franchise’s pivot from analog to digital, from landline terror to algorithmic notoriety.

Scream 7, by contrast, gestures toward cultural correction. In a late-2020s climate increasingly skeptical of hyper-digital performativity and increasingly nostalgic for tactile authenticity, this installment feels almost deliberately analog in spirit. The satire is restrained. The violence has weight. The mystery mechanics are foregrounded. If Scream 4 bridged the franchise into the digital age, Scream 7 gently guides it back toward its roots. Both are recalibrations—but pulling in opposite technological directions.

It would be naïve to ignore the production context that shaped this film. Melissa Barrera’s departure following her public political statements altered the series’ trajectory and necessitated a creative reset, with Kevin Williamson returning to write and direct. Freedom of speech is foundational—but not without professional consequence within corporate filmmaking. The result is a film structurally distinct from what entries five and six were building toward.

More concerning than the controversy itself is the critical climate surrounding the film’s release. Its unusually low Rotten Tomatoes score reads less like a measured assessment of craft and more like a referendum on production politics. Evaluated on narrative mechanics, tonal discipline, and franchise coherence, Scream 7 is far from a failure. It is focused, structurally sound, and far more aligned with the franchise’s DNA than its aggregate score suggests.

This return to form may also be more culturally resonant than some critics assume. There is a growing appetite—particularly among younger audiences—for analog aesthetics and classical genre storytelling. Eli Roth’s Thanksgiving proved that an original slasher can thrive in the 2020s. Scream 7 demonstrates that a legacy slasher can endure by remembering what made it compelling in the first place.

In retrospect, Scream 7 may not be the boldest chapter in the franchise—but it may prove to be one of the most necessary. It restores the mystery spine. It reinstates consequence. It reminds us that Ghostface works best when the blade cuts both ways—satire and sincerity, humor and horror. The original remains untouchable. But longevity in horror does not come from constant reinvention. It comes from understanding when to sharpen the knife rather than redesign it.

And sometimes, survival is less about evolution than about reclaiming your identity.

Ryan is the general manager for 90.7 WKGC Public Media and host of the show ReelTalk “where you can join the cinematic conversations frame by frame each week.” Additionally, he is the author of the upcoming film studies book titled Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror. After teaching film studies for over eight years at the University of Tampa, he transitioned from the classroom to public media. He is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Follow him on Twitter: RLTerry1 and LetterBoxd: RLTerry