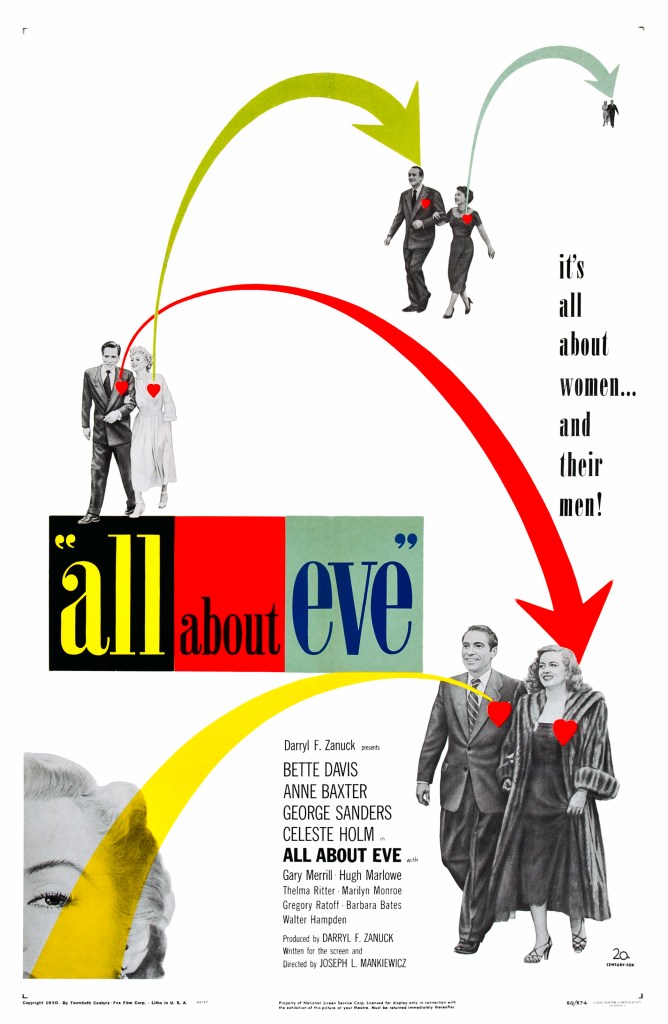

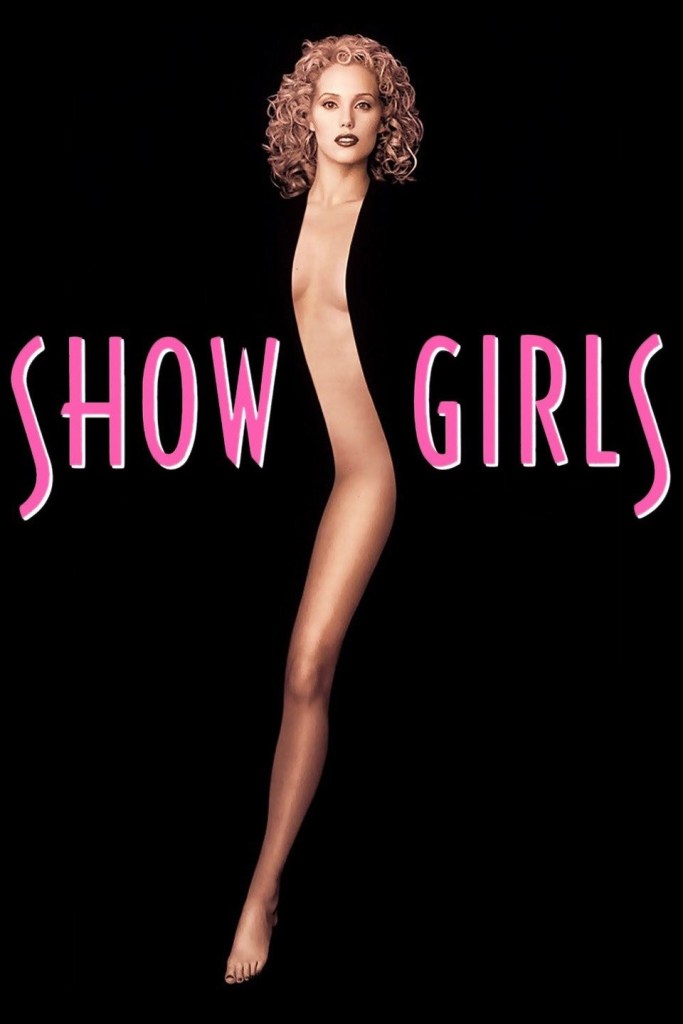

Celebrating the 75th anniversary of All About Eve and the 30th anniversary of its descendent Showgirls.

“Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a [gripping read].” All About Eve is celebrating 75 years of cinematic excellence, and its audacious descendant Showgirls is marking 30 years of—well—let’s call it a complicated legacy (but I like to think of it as a misunderstood masterpiece). Whether you’re among those who believe Showgirls was simply ahead of its time or still see it as a camp disaster, one thing is undeniable: without All About Eve, it likely wouldn’t exist at all. For 75 years, All About Eve endures as both a pinnacle of Hollywood storytelling and a cautionary tale about the intoxicating—and corrosive—nature of ambition. Its exploration of fame, manipulation, and the cyclical hunger of show business feels as sharp and relevant today as it did in 1950, resonating in an era where social media stardom and viral fame echo the same relentless pursuit of the spotlight.

Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Oscar-winning classic, based on Mary Orr’s short story The Wisdom of Eve, has captivated audiences for 75 years with its seamless blend of timeless entertainment and biting critique. More than just a backstage melodrama, All About Eve dissects the intoxicating allure—and devastating cost—of stardom and ambition with wit as sharp as a perfectly aimed dagger. Its dialogue remains some of the most quotable in film history, its characters as vivid today as they were in 1950, and its observations about the ruthlessness of fame feel eerily prescient in our age of viral sensations and manufactured celebrity.

Since its release, All About Eve has inspired countless films and remains a cornerstone of Hollywood storytelling. But what does it mean to you? What makes it special or stand out after all these years? Perhaps you regard it simply as an iconic classic; or perhaps you find in it something more personal—an echo of ambition, vulnerability, or the razor’s edge of success. From its sparkling, acidic dialogue to some of the most quoted lines in cinema including the immortal “Fasten your seatbelts. It’s going to be a bumpy night,” Margo Channing’s spirit lives on. So much for her fear of being replaced by “the next bright young thing;” she is as alive today as she ever was. Serving as both a love letter to and critique of the theater and the entertainment industry, Mankiewicz’s film exposed the timeless cost of ambition and the ruthless cycles of celebrity—lessons that still resonate in an era obsessed with youth and virality. Arriving at the twilight of Hollywood’s Golden Age, this masterpiece continues to epitomize the glamorous yet perilous dance between artistry and stardom. Beyond its historical and industrial significance, it endures because it connects—visually, emotionally, and thematically—with anyone who has ever feared obsolescence or dared to reach too high.

Part of what still fascinates audiences is the film’s layered structure and the magnetic performances at its heart. Bette Davis’ Margo Channing is so perfectly pitched that viewers often forget they are watching a performance at all–there is a lot of Davis in Channing much in the same way there was a lot of Gloria Swanson in Norma. Neither legendary actress was their respective screen personas, but there were parallels that empowered genuine, sincere deliveries. Mankiewicz wove aspects of Davis’ own persona—her wit, her commanding presence, her refusal to fade quietly—into Margo’s characterization, yet Davis was both exactly Margo and not her at all. Much in the same way Gloria was both Norma and not at all–at the same time, as both iconic films were released in 1950. Davis seized the role as a triumphant reinvention, turning what could have been a caricature of the “aging diva” into a fully realized, vulnerable, and dangerously sharp woman. Like Margo, Davis had weathered the changing tides of the industry. But in true Bette Davis fashion, rather than retreat into the past, Davis embraced this role as an opportunity to reassert her dominance in the art form she loved.

If you’re looking for a real-life “Margo Channing,” aside from the real-life individuals on which Mary Orr based her original short story published in Cosmopolitan magazine, you’ll find shades of her in many stars of the era who feared being replaced by someone younger and hungrier, yet few carried that fear with the same poise and theatricality as Davis. Her performance reminds us that the ghosts of obsolescence do not have to haunt you if you learn to wield them as power instead of surrendering to them. Davis did exactly that, continuing to reinvent herself on stage, screen, and television for decades to come. All About Eve endures not because it is frozen in the amber of classic cinema, but because it still speaks—cuttingly, wittily, and poignantly—to the ever-revolving stage of fame and the cost of staying in the spotlight.

Who, then, were the real-life figures that inspired Mary Orr’s original story? While Orr never definitively identified the proud theatrical star and the manipulative upstart who became the templates for Margo (originally “Margola”) and Eve, her own comments—and those of her contemporaries—point to a blend of influences. Viennese actress Elisabeth Bergner and Broadway legend Tallulah Bankhead are often cited as inspirations for Margo, while actress Irene Worth and a “terrible woman” (Bergner’s own words) named Ruth Maxine Hirsch—who performed under the stage name Martina Lawrence—are believed to have shaped the character of Eve: the fan-turned-assistant-turned-understudy-turned-star. Though no single pair of women can be pinpointed as the Margo and Eve, the fact that these characters emerged from a patchwork of real events and personalities only deepens the story’s enduring intrigue.

All About Eve endures as timeless because at its core, it is less about a particular moment in Broadway’s Golden Age and more about ambition, ego, and the ruthless pursuit of relevance—dynamics that still fuel the entertainment industry today. Strip away the mink coats, rotary phones, and cigarette smoke, and the story of a hungry ingénue inserting herself into the life of an aging star could just as easily unfold in the Instagram era, where image management and backstage maneuvering are just as cutthroat. The barbed wit of Mankiewicz’s script remains startlingly fresh. Its sass, frankness, and playful cruelty dance along the liminal space between youth and experience, sincerity and manipulation, still lands with a sting. With only a few cosmetic updates, All About Eve could be set in present-day Hollywood, Broadway, or even influencer culture, and it would be no less thoughtful, provocative, or entertaining.

The themes of All About Eve find a striking mirror in today’s social media and influencer culture, where the pursuit of fame and relevance plays out in real time before millions. Just as Eve Harrington ingratiates herself into Margo Channing’s circle to climb the theatrical ladder, influencers often build careers by aligning with established figures—sometimes with genuine admiration, other times with calculated opportunism. The tension between youth and experience, central to the film, is equally present online, where younger creators often supplant veterans by capturing fleeting trends, while older figures wrestle with maintaining relevance in an environment that prizes novelty.

Whether set in the past, present, or in projections of the future, explorations of image versus reality resonate powerfully, including in today’s digital landscape wherein curated personas can mask ambition, manipulation, and insecurity. Even the razor-sharp verbal sparring of All About Eve has its equivalent in the witty clapbacks, subtweets, and public callouts that fuel today’s digital drama. In both cases, the stage—whether Broadway or Instagram—is a battleground where applause, followers, and validation dictate survival.

This enduring clash between performance and reality underscores how stories of ambition and rivalry are continually reimagined across eras and mediums. From the lights of Broadway to the doom scrolling of Instagram, the hunger for validation and the willingness to deceive—or be deceived—remains constant. It’s no surprise, then, that later films would tap into similar veins of that which run through All About Eve, though with radically different tones and settings.

Over the decades, Paul Verhoeven’s notorious Vegas fever dream Showgirls has been labeled everything from a misunderstood masterpiece to one of the worst movies ever made. What was initially dismissed by critics as vulgar excess has since been reappraised by some as a biting, if over-the-top, satire of the entertainment industry’s exploitation of women, ambition, and sexuality. Its brash depiction of the climb from obscurity to stardom mirrors that of All About Eve, though filtered through neon lights, gratuitous spectacle, and camp sensibilities. That tension—between tawdry sensationalism and incisive critique—is precisely what keeps Showgirls alive in the cultural imagination, ensuring its legacy as both a cautionary tale and a cult phenomenon.

Showgirls operates as a satire of entertainment culture and the performers who are both consumed by and complicit in its machinery. Where Eve Harrington’s quiet scheming exposes the ruthless politics of the theater, Nomi Malone’s raw ambition lays bare the transactional underbelly of Las Vegas spectacle. Both films hinge on the same unsettling truth: in an industry where visibility is power, identity itself becomes a performance. What distinguishes Showgirls is how it weaponizes vulgarity and excess as a form of critique. Its glitter, nudity, and violence were long dismissed as gratuitous, yet in hindsight these elements function as deliberate provocations; it can be read as an aesthetic that is designed to mirror the gaudiness and cruelty of the world it depicts. Seen today, the film feels strangely ahead of its time, anticipating the rise of influencer and social media culture where personas are manufactured, scandals are commodified, and fame can be won or lost overnight. Reconsidered in this light, Verhoeven’s so-called disaster reveals itself as a smart, if abrasive, cultural text: one that understands spectacle not as decoration, but as the very language of modern celebrity.

At its core, Showgirls dramatizes the hollow cost of chasing celebrity. Nomi’s relentless climb through Las Vegas’s entertainment machine is marked by betrayal, objectification, and the constant demand to reinvent herself in service of spectacle. Each rung of success—dancing at the Stardust, becoming the star attraction—promises fulfillment, yet delivers only greater alienation. Verhoeven underscores how ambition, when tethered exclusively to validation and visibility, erodes one’s sense of self until little remains beyond the performance itself. By the film’s conclusion, Nomi is left with the trappings of stardom but no genuine connection, no lasting satisfaction, no identity untouched by the corrosive gaze of the industry.

In this way, Showgirls finds an unlikely kinship with All About Eve. Where Margo Channing wrestles with the costs of aging in an industry that worships youth, Nomi embodies the illusion that ascension itself will satisfy the hunger for recognition. Both films reveal the same truth: the spotlight is never enough. Whether in the refined milieu of Broadway or the gaudy spectacle of Vegas, ambition without grounding in humanity becomes corrosive, leaving its pursuers hollow even in triumph. It’s that shared cynicism—and tragic insight—that makes Showgirls more than the vulgar provocation it was dismissed as, and positions it as a worthy, if wildly flamboyant, descendant of Mankiewicz’s classic.

Seventy-five years after its release, All About Eve still cuts to the heart of what it means to seek validation under the bright lights, and thirty years on, Showgirls shows us that the hunger has only grown more voracious, more theatrical, and perhaps more desperate. Both films, in their vastly different registers, remind us that the pursuit of fame is never simply about talent or opportunity—it is about the sacrifices made along the way, and the hollow victories waiting at the top. If All About Eve gave us the blueprint for understanding the price of ambition, Showgirls showed us what happens when that price is paid in full. And as long as there are stages to stand on—whether Broadway, Las Vegas, Hollywood, or TikTok—the lessons of both films will remain hauntingly, and uncomfortably, relevant.

For the companion radio/podcast episode to this article, check out my show ReelTalk on WKGC Public Media. You can listen through Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. Links provided below or, in your podcast service, search WKGC Public Media.

Ryan is the general manager for 90.7 WKGC Public Media in Panama City and host of the public radio show ReelTalk “where you can join the cinematic conversations frame by frame each week.” Additionally, he is the author of the upcoming film studies book titled Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror. After teaching film studies for over eight years at the University of Tampa, he transitioned from the classroom to public media. He is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Follow him on Twitter: RLTerry1 and LetterBoxd: RLTerry