All the Horror Presents Women in Horror Month

All the Horror Presents Women in Horror Month!

During the month of February, a group of podcasters and writers, including yours truly, are highlighting many leading women and final girls of horror films! Be sure to follow

@AllTheHorror18 on Twitter for the links to all the podcasts and written articles from the participants in this limited time engagement. Each week starting on February 4th, I will provide you with a character analysis of some of my favorite women in horror, and hopefully some of yours too! For the sake of simplicity, I will add each article to this blog entry. The horror genre, from its inception, has consistently been the most candid, progressive, and powerful of all the genres. Furthermore, it possesses an innate ability to be more truthful than a typical drama because we give it permission to challenge us in intimate ways. While there are many reasons for the timelessness and thought-provoking nature of horror, we are here to specifically focus on the women of horror. You don’t want to miss any of the great content coming your way during the month of February. Enjoy!

- Clarice Starling (Feb 4)

- Ellen Ripley (Feb 11)

- Nancy Thompson (Feb 18)

- Annie Wilkes (Feb 25)

For my 2020 article, click

HERE.

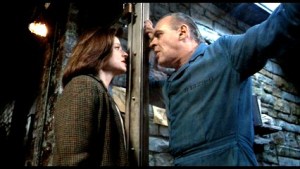

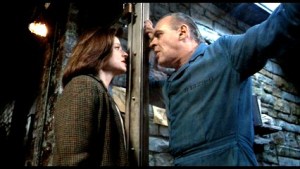

Clarice Starling

When I think of strong female characters in horror, one name instantly jumps to the front of my mind, Clarice Starling (played by Jodie Foster) in

The Silence of the Lambs. Not only is she, in my opinion, the single most important female character in all horror, she is one of the most influential and important female characters in all of cinema! Perhaps there is no greater example of a dynamic, unassailable female central character in a horror film. Not only is the character one to be revered and admired, but Foster won the Academy Award for Actress in a Leading Role for her portrayal of Clarice. Incidentally,

The Silence of the Lambs is only one of three films to win the Big 5 Academy Awards (Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, Screenplay). But we are here to analyze the character of Clarice.

Even before we learn anything about Clarice’s wit and intellectual prowess, we witness her hard-working nature on the obstacle course in Quantico, VA, well-known for being the home of the FBI training academy; her status as an FBI academy student is solidified by her shirt. Furthermore, we observe her holding her own in a field dominated by men. This opening sequence of shots is important to visually convey Clarice’s raw determination to achieve what she wants. We don’t have to know the particular area of the FBI in which she wants to specialize, all we need to know is that she will stop at nothing to realize her aspirations. Even when she dies in a simulation, she does not excuse her lack of response, but she states why she died in a purely objective way. We learn later on in the film, that Clarice is haunted by a childhood trauma of a combination of her father dying during a burglary and the slaughter of lambs at her uncle’s ranch. She is driven by her desire to protect and free the innocent from dangerous humans in the world. Hence why she pursues a career as a special agent in the FBI. Her career aspirations are a means for her to overcome the emotional chaos of her childhood by stopping at nothing to land her position in the Behavioral Sciences division of the FBI under Jack Crawford.

One clear motif throughout these opening scenes is this idea of a woman in a man’s world; moreover, it’s the depiction of female agency. Although not one of the most memorable quotes from the film, Clarice’s line “If he [Buffalo Bill] sees her as a person and not just an object, it’s harder to tear her up” this is the line that highlights this often overlooked theme central to the plot of the film. Moreover, there is recurring imagery of the

male gaze and the defiance thereof from colleagues, superiors, officer counterparts, and Dr. Lecter. Entire articles have been written on cinema and the male gaze, and I don’t have time to go into all the details in this character analysis of Clarice; but for the majority of its existence, cinema has reflected heterosexual male dominance–objectifying women–whether its overt through action or subtle through subtext. However,

The Silence of the Lambs combats this practice by subverting the voyeuristic male gaze by forcing the audience to see Clarice (and all women in the film, by extension) as unique individuals and not objects.

One of the most admirable aspects of Clarice is her well-rounded nature as a character. She shows signs of strength, vulnerability, innocence, determination, independence, and a willingness to learn. By way of the manner in which Director Jonathan Demme chose to have the male characters, friend or foe, look directly into the camera lens when addressing Clarice and Clarice looking just off camera when responding predisposed us to identifying with Clarice’s character–we place ourself in her shoes. As the male characters look into the camera addressing Clarice, we feel that they are gazing at and addressing us. But my Clarice looking away from the camera lens, she visually subverts the male gaze as she becomes the one with the power in the scene. Great way to visually communicate this theme to the audience. But it’s more than just communicating a theme, this action gives Clarice power often attributed to male characters therefore increasing her level of dominance.

Clarice is everything that we want in a horror or thriller protagonist. And the beauty of this film is that it is both a horror and suspense thriller. And she works as an admirable, brave, and authentically human for both. More than a strong protagonist, she is a feminine icon who needs no qualifiers. Simply stated, she broke the mold of what was expected of female protagonists in general, and specifically horror. All the while she is working diligently at tracking down Buffalo Bill and learning how to best work with Dr. Lecter, she faces both overt and subtle discrimination but does not flinch a muscle. It’s her sheer chutzpah, authenticity, and respect for Dr. Lecter that endears her to him. Has she shown weakness, a facade, or patronized Dr. Lecter, it’s entirely possible that he may not have taken a liking to her. He realized that she was truly a match for his wits, a worthy opponent. Continually, she displays strength of character and impressive intellectual prowess. Well written central and opposition characters often have a symbiotic relationship (that was partially highlighted in David Gordon Green’s

Halloween), one cannot truly exist without the other, or at least one is not as interesting without the other. The more interesting Clarice is, the more interesting Hannibal is. They both display traits that complement one another. It’s this complementary nature that Dr. Lecter finds intriguing and worthy of his admiration. And in the same way, Clarice is attracted to certain qualities of Dr. Lecter that prompt her to respect him as an individual despite his heinous crimes.

A couple of examples from the film in which men feel threatened by or undervalue the level of excellence that is found in the person and career of Clarice can be found in Dr. Chilton and the sheriff’s deputies in the funeral home after the body of Buffalo Bill’s first victim was discovered at which she is sidelined by Crawford and gawked at by the deputies. When Dr. Chilton learns that Clarice was able to connect with Dr. Lecter in her brief when he’s been selfishly attempting to for years, he seeks to subvert Clarice’s efforts, to no avail thankfully. His masculinity was threatened by a female, and Chilton was not about to have that. Good thing he got his comeuppance. When in the funeral home/morgue of Frederica Bimmel, Crawford intentionally sidelines Clarice because he felt the details were too disturbing for her; she shows him by taking control of the room by forcing the sheriff’s deputies out of the room because she has it under control and gets up close and personal with the victim. This is also the scene where she finds the telltale death’s head moth that has become synonymous with this film. In that scene we witness Clarice recognizing her unequal treatment, and rises to the occasion to show that she would not stand for it because she was objectively qualified to continue in her work without hand-holding or patronization.

Outside of the two etymologists, the only male character to not show any signs of misogyny nor gender discrimination is Dr. Hannibal Lecter himself. As highlighted earlier, he recognized her as a formidable opponent in his mind games. Although he certainly tries to get in her head, make her feel uncomfortable, and face her past demons to

silence the lambs, nothing he does is motivated out of sexual desire or gender discrimination. Nothing in her role is truly defined by her gender. In fact, much like the character of Ripley in

Alien was originally slated for a male character, the character of Clarice Starling could also be a male. I am glad it wasn’t because the narrative would lose some power. But the point is, that she is in no way defined by her gender, instead is defined by her integrity, character, and intelligence.

Even when taking on “masculine” traits and existing within a male dominated field of work, she never ceases to remain a feminine character. She and

Alien‘s Ripley share this in common. Jodie Foster states in reference to her iconic character, “Clarice is very competent and she is very human. She combats the villain with her emotionality, intuition, her frailty, and vulnerability. I don’t think there has ever been a female hero like that.” The character of Clarice Starling is one that should serve as a model for other female central characters. She contributed significantly to the world of cinema, but specifically the American horror film.

Ellen Ripley

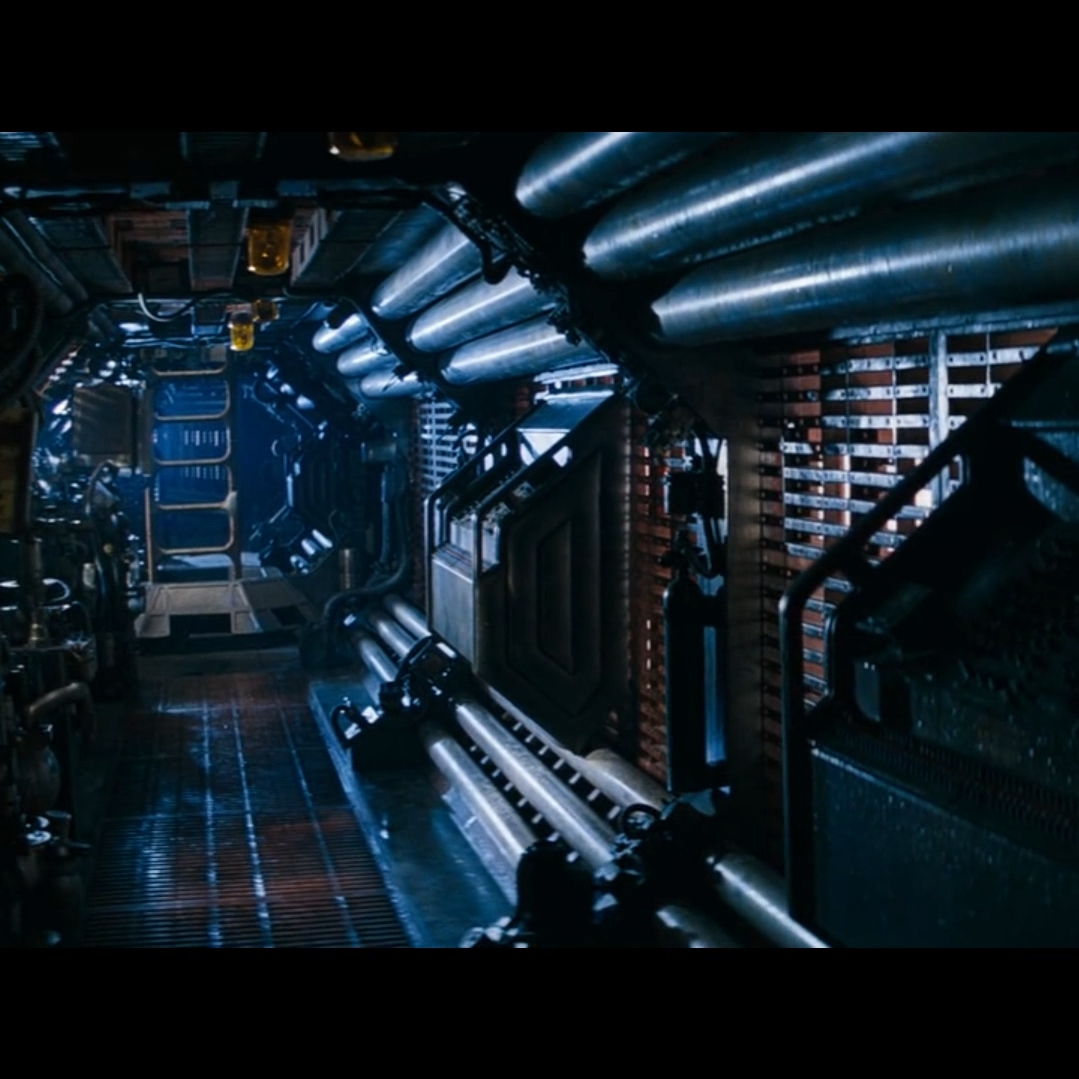

This. Is. Alien. You are with. Sigourney Weaver. Aboard–the starship–Nostromo. Caution. The area you are en-ter-ing is extremely dan-ger-ous. Something has gone wrong…

This. Is. Alien. You are with. Sigourney Weaver. Aboard–the starship–Nostromo. Caution. The area you are en-ter-ing is extremely dan-ger-ous. Something has gone wrong… If you get why I punctuated that the way I did, then you remember the

Alien scene on the former

Great Movie Ride at Disney’s Hollywood Studios (oh how I miss that attraction). We cannot talk Women in Horror without analyzing the boundary busting, glass ceiling breaking Ellen Ripley (played by Sigourney Weaver). Ridley Scott’s science-fiction horror masterpiece that convinced us that “in space, no one can hear you scream” is still the definitive science-fiction/space horror film. Sitting between

Halloween and

Friday the 13th, this film came as a surprise for the horror genre because it countered the direction that the horror genre was going by reimagining the emerging slasher genre in a setting that is more terrifying and limiting than a house or town in which a serial killer is slaughtering teenagers. The strength of this movie is not in the Xenomorph, the effects (albeit great), or even the first characters you spend time with in the film, the strength of this film is in the ineffaceable character of Ripley.

Although she is, for all intents and purposes, not even on our radar for nearly 45mins into the film, following a tragedy, she is thrust into the forefront of this mission. Scott’s

Alien dared to challenge the status quo in order to deliver the first female action hero, and place her in center stage. The long and short of it is that Ripley subverts the typical science-fiction hero trope to embody both the feminine and masculine to redefine what a hero is within the sci-fi/horror genre. Breaking gender norms for the time, she was neither arm candy, simply a side kick nor required rescuing by a male character. Her character and actions were not defined by gender. She is our final girl, and so much more. Not only did the character of Ripley contribute significantly to horror, she also broke ground for female heroines in the world of cinema at large.

Your central character need not always be the first or second character we encounter in a screenplay. This is true with Ripley as she emerges as the central character midway through the film. However, we are given hints at her destiny throughout the first act in subtle ways. It was important to the plot to establish her as a woman in order to make her actions later on in the film so kickass and assumption shattering. Had she been seen as “masculine” or strong from the onset, then we would not be as impressed with her actions–we would expect them. Part of her power as a strong female character in horror is taking what we assumed about her (or a female character in general) and subvert our predisposition. Whereas Ripley is not the first female heroic character in a horror film, she is one that never becomes subjected to the male gaze or becomes some fantasy version of a woman. Even though female heroic characters who wear sexy clothes, wield phallic guns, or use their bodies as femme fatals can be strong characters, they are still some heteronormative fantasy for a male screenwriter or director.

Essentially, the aforementioned female characters lack an authentic humanity. Ripley is strong, vulnerable, independent, scared, mortal; these elements that make her believably human. There is so little suspension of disbelief in her character that she could nearly exist in real life. Furthermore, her character is incredibly complex; she exhibits strong intuition and intelligence, chutzpah, is brash, talks about PTSD, outspoken, rigidly wants to go by the book instead of saving a man’s life, has a natural beauty but doesn’t spend much time on hair or makeup. All these traits portray someone who has incredible depth and dimension. She is a survivor. No matter how grizzly, messy, constricting, or frightening her soundings become, she remains steadfast, collected, and brave. As the 1970s saw many changes in censorship, ratings, guidelines, etc., the ability to show gorier, more visceral body horror special effects, and on screen violence allowed Scott to confront the character of Ripley with cinematically innovative ways to test her resilience and survivorship.

The character of Ellen Ripley is also a strong pillar of the American horror film by virtue of her representation of gender politics. Even before it became popular, in more recent times, to use both male and female characters in motion pictures as a conduit to comment on the state of affairs for a particular group within our society, Ridley Scott crafted a visual masterpiece that did just that. Highly innovative, forward thinking, and progressive. The subtext of the film confronts us with a woman trying her best to fit into a man’s world. In addition to that subtext, research into the screenplay for this film shows that all the characters were written as gender neutral. Interesting stuff, right?!? Another gender-related observation in the character of Ripley, is her both metaphorically and physiologically clothing herself in masculinity all while remaining a women. In one scene, Ripley steps into a space suit. And this space suit can be read as Ripley playing the role of a man while remaining a women at her core in order to challenge the patriarchal system to prove that she is capable of anything that a masculine hero is.

Ripley is a highly intelligent character, realizes that about herself, and does not allow herself to be patronized or undermined. She does her job aboard the Nostromo like a legit boss. She knows procedure and protocol, and will follow it in order to protect her crew. Figuratively, she is protecting the ship from being willfully penetrated by a foreign object. This could be read as a commentary on rape. She is forcefully overruled, and we all know what happens next. Further commentary depicts male characters “forgetting” that Ripley is the senior officer. But because she is female, they feel they know better. I bet they wish they had followed her orders. Although much of what I’ve written deals with the masculine qualities of Ripley, her character would not have been as powerful a character if it wasn’t for her feminine side as well. When all hell is breaking loose, she soothes the nerves of the crew and offers comfort. Exemplary motherly qualities. Had a man been in her role, then he would most likely have not exhibited such love for the crew. Her success as a hero has as much to do with the touch of a women as it does the chutzpah of a man. Another motherly quality found in Ripley is her persistent urge for the crew to function as a group. Through the brilliant cinematography, we are consistently shown a group that is fractures and continually fails to band together until it is too late. Interestingly, each character meets his or her demise because of a tragic flaw and failure to group together to function as ONE crew instead of self-centered individuals. Had the group functioned as one, then more may have survived. This hypothesis is witnessed in the Ripley in Act 3 because she essentially embodies all the good qualities found in the other characters (think Captain Planet). She combines what everyone did well into one character. That is why she is the final girl. Only by combining all the qualities of the crew was she able to go toe-to-toe with the Xenomorph killing machine.

There are actually three prominent female characters in

Alien. Ripley, the Xenomorph, and The Nostromo. Although Ripley is our central character, I would be remiss to not mention the other two that could be analyzed individually themselves. Much like Ripley exhibits both masculine and feminine characteristics, so does the Xenomorph with a mouth that oscillates between vaginal and phallic in nature. And finally, The Nostromo ostensibly gives birth to all the astronauts at the beginning of the film; and therefore could be referred to as the

mother ship. Playing around with gender does not stop there. The facegrabber impregnates a male character and he gives birth to the Xenomorph. Underscoring so many elements and conflicts in this film is this idea of subverting gender identity with the intent to horrify by tapping into primal heteronormative fears. And let’s face it, child birth is terrifying. Unfortunately, all the sequels failed to live up to the substantive nature of the original and devolve into a generic futuristic action-adventure series; but the original

Alien delivered a nightmare-inducing “haunted house” movie set in the far reaches of space where “no one can hear you scream,” and provided us with the breakthrough character of Ellen Ripley.

Nancy Thompson

“Whatever you do, don’t fall asleep.” More than a final girl, Nancy is a

live girl. While

Halloween‘s Laurie Strode often gets credit for being the original

final girl, and with good reason, a solid argument could be made that

A Nightmare on Elm Street‘s Nancy Thompson (played by Heather Langenkamp) is the OG final girl. For my third character analysis for Women in Horror Month, I want to explore the character of Nancy in

A Nightmare on Elm Street. Unlike the previous two analyses, Nancy is not yet an adult, pursuing her career in law enforcement or the far reaches of space. She is an

every-man with whom we can identify, because we were all, or maybe still are, teenagers facing everyday struggles with our relationship with our parents, love interests, and our friends. With death surrounding her on all sides, she powers through the grave conflict, to face her nightmares, and defeat the Dream Master himself Freddy Krueger. Well, set him back anyway. Haha.

Unlike Laurie Strode, Nancy is not the final girl by default; she completely

Home Alones Freddy and continually fights back without ever backing down. She takes an

active role in ensuring her survival. Furthermore, no one comes in to aid in her rescue or the defeat of Freddy; Nancy is alone in her endeavors. Despite her strength of character and resilience, she is largely overlooked by fans. Her co-star Freddy Krueger (played by the incomparable Robert Englund) steals the spotlight. Although Freddy is my favorite horror slasher villain, I often wonder why Nancy doesn’t get the same treatment that Laurie gets in

Halloween. Making her debut in 1984’s

A Nightmare on Elm Street, Nancy appears again in

Dream Warriors, and

New Nightmare (as Heather, but she is still very much Nancy). Grab your coffee, and stay up with me as we explore Nancy Thompson!

We aren’t given much insight into the degree to which Nancy excels in school, but she is undoubtedly quite the scholar! Not that whether or not she is a member of the honor society makes a difference, but it does aid in showing us that she possesses superior critical thinking skills. If not for her brilliant combination of street and book smarts, she may not have survived this very real nightmare. Unlike many final girls who are often on the defensive, she spends much of the movie on the offense–she goes looking for Freddy. Who does that??? Nancy, that’s who! We witness Nancy read books to learn more about dreams and newspapers to learn more about Fred Krueger; furthermore, she experiments with booby traps and methods to remain awake or force sleep. Resilient, resourceful, and ready. A great alliteration to describe Nancy. Her survival does not happen by default or through a deus ex machina, she survives through grit, determination, and a willingness to learn and place herself in harm’s way. It’s this notion that she transcends what we think of as a final girl to even go so far as to subvert our predispositions. Whereas typical final girls merely survive, Nancy takes control of the Freddy conflict in a revenge fashion to win. “I’m into survival,” as Nancy so brilliantly puts it.

Nancy is not concerned with innocence or following the rules to maintain the status quo. While she still may be a “good girl,” she is not concerned with playing the good girl card in order to somehow survive Freddy. On display in this film is the cinematic and literary construct of the maiden turned warrior. We witness a psychological growth arc paralleling a physiological transformation, in the character of Nancy, that takes her from everyday teenager, complete with the angst, to heroine. And her inner-personal journey is not without its own obstacles and conflict. At every step of the way, Nancy encounters loved ones in her life (be they family or friends) who consistently do not believe in her–until it is too late. All of Elm Street doesn’t believe her, but she knows that Freddy is killing the Elm Street kids in their nightmares, and she is going to prove it and stop him.

One of the messages that I preach to my screenwriting class is the importance of communicating character thoughts and feelings visually (only write what you can see), and Wes Craven does precisely that to communicate how everyone feels about Nancy’s claim that Freddy is back. For example, Nancy’s mother violates her body by subjecting her to sleep tests and even making her a prisoner of her own home with the bars on the windows. A close reading of the imagery associated with the trauma Nancy experiences can be read as a metaphor of adolescence, transitioning from childhood into adulthood. Whether experiencing direct or implied trauma from Freddy, her family, or friends, she endures gaslighting, imprisonment, mental rape, and attempted murder all within the confines of the home–and more specifically–the intimacy of the mind. Not only does Nancy prove that she may in fact be the definitive final girl, though overshadowed by Laurie, by her active role in ensuring her survival against Freddy, she also survives psychological and physiological trauma enacted upon her by loved ones. Her voice was silenced, her path to escape was barred, and her claims that Freddy returned from the dead into the dream world were completely dismissed. This parallels what many women face every day–they are not taken seriously or they are patronized. Her character is a metaphor for what many women face daily.

One may conclude that Nancy lacks the vulnerability and (heteronormatively speaking) feminine nature that is required, traditionally speaking, of a final girl. Certainly the preceding paragraphs skew toward ultimate horror badass, but the beauty of Nancy’s character is that she grows from a vulnerable female teenager into the final girl that we know today. Her all-too-human feminine vulnerability is shown through her white pajamas with pink roses, her teenage angst, crying when she is upset or feels dismissed, and she experiences the emotional rollercoaster that we all, but especially teenagers, ride. After rewatching

A Nightmare on Elm Street in the cinema for a 35th anniversary special one night only screening, I was reminded of just how much of a girl she is throughout the whole movie. Not only does she get scared and cry and even take cover behind Glen early on in the film, but she also wears clothes that reinforce the idea that she doesn’t need to take on masculine traits in order to defeat evil. Her character transformation occurs in the mind and she proves that a girl can do anything that a guy can do. She does not allow the constant barrage of dismissal or people telling her that she’s crazy to detour her from what she knows to the nightmarish truth.

Further distinguishing Nancy from other final girls is the manner in which she does defeat Freddy Krueger. Whereas we assume she hasn’t had sex with her boyfriend Glen and does not appear to use illicit drugs or undermines authority for her own selfish pleasure, she does not defeat Freddy because she is a “good girl.” Nancy relies upon resilience, wit, and confidence; ultimately, she defeats Freddy by refusing to give him anymore of her emotional energy (a feminine trait) instead of wielding some phallic weapon like a knife, machete, or bludgeoning tool. Unlike other final girls whom become a de facto male character during the showdown, she remains committed to her femininity. Unlike the gender politics of

Alien, the character of Nancy doesn’t oscillate between feminine and masculine. Instead, she transforms from normal, innocent teenager with many of the same familiar and friendship conflicts we face to the brave, determined, proactive smart heroine that defeated Freddy (temporarily anyway), all while never shifting from her typical female behaviors and identity.

After

Freddy’s Revenge (and you can hear my review of this installment on

Cocktail Party Massacre), Nancy returns in

Dream Warriors as a graduate student working and studying at a psychiatric hospital. She may have exchanged her pink rose pajamas for 80s power suits, but she is still the same Nancy. The Freddy experience has certainly had an effect upon her, but she has taken that traumatic experienced, harnessed the power of it and channeled it in a positive direction to help others who are experiencing psychological trauma that has real world physical traits. Specifically, she researches the mental and physical effects of nightmares. Without diverting into a plot analysis of this tertiary installment in the franchise, she is able to successfully transfer her strengths to the Elm Street children. Completely unrelated to the character of Nancy, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention my favorite Freddy quote of all time that appears in this movie, “welcome to prime time, bitch!”

Even before meta horror became popular, and Wes Craven himself would write and direct the definitive meta horror

Scream two years later, he returned with full creative control to the

Nightmare franchise to write the final chapter (until

Freddy vs Jason and the awful 2010 remake) in the reign of Freddy, he gave us

New Nightmare. Despite her death in

Dream Warriors, “Nancy” stars once again in the

Nightmare on Elm Street third chapter

New Nightmare. Nancy is in quotes because it is the actress Heather Langenkamp as a character in this meta

Nightmare film. She is Heather but very much Nancy all at the same time. In addition to Heather playing herself playing Nancy, Robert Englund plays himself playing Freddy. Other actors/characters from the original

A Nightmare on Elm Street have appearances as well. In this film, Heather faces her reality fracturing as a nightmarish specter from her past comes to haunt her. It looks like Freddy, but it is much more sinister. What I love about Heather/Nancy is the fact that she channels her Nancy from the original and

Dream Warriors. But she doesn’t phone in her performance or give us the same character. Her “Nancy” has grown. One of the biggest differences between Nancy and Heather is that Heather is now challenged with protecting her son at all costs. Through her passion, wit, confidence, and unyielding ability to face the darkness head on, she confronts Freddy to once again, become the final girl.

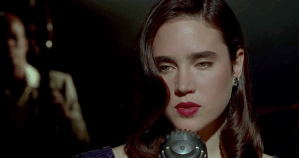

Annie Wilkes

Do your ankles hurt just at the thought of Annie Wilkes? Well, they should because she is one of the most terrifying Women in Horror ever. Perhaps you do not remember her by name, but you most likely know the film

Misery. Based on the best-selling novel by Stephen King,

Misery is widely regarded as one of the most terrifying psychological horror films ever. Directed by Rob Reiner, it stars then-newcomer Kathy Bates as Annie Wilkes. Playing opposite Kathy is James Caan as celebrity author Paul Sheldon. Just a quick note, the sultry Lauren Bacall also makes an appearance in this horror film as Sheldon’s agent. While my other character analyses for Women in Horror Month focussed on final girls, for this final entry, I desired to explore a truly sinister female character whom captivated us with her outstanding performance. In a quintessential Hitchcockian fashion, Rob Reiner crafts a phenomenal adaptation of the King novel that mostly takes place in one location. But this one location houses two indelible characters, one of which is a wildly disturbed and frightening fangirl. Annie convinced us that anyone who claims to be your No.1 fan may actually be your No.1 worst nightmare. Next time a nondescript motherly figure invites you to her picturesque cabin in Colorado, you may want to consider staying at the local Holiday Inn instead.

Talk about a character with incredible depth! Annie Wilkes is one of those exemplary characters in horror that provides ample opportunity to apply critical lenses to analyze her psychology and sociology. Clearly she displays signs of psychopathy, but there is so much more to her character. And those layers are what makes her one of the most terrifying characters in horror film history. On the surface, she is a monster-like human; but beneath that sociopathic behavior, she is clearly suffering from severe mental disorders brought on by past trauma. Collectively, we can surmise that Annie’s past traumas left her feeling that everyone and everything is out to get her. Therefore, she runs a countryside farm in mountainous Colorado away from everyone. Her only interaction with outsiders is when she has to run to town to pickup food and supplies. In addition to her mental disorders, she also displays signs of agoraphobia. Although some of her mental disorders have direct impact on her violent nature, other disorders are largely indirectly responsible, such as her likely obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Evidence supporting this can be seen in her immaculately clean and organized house. Her OCD contributes significantly to her obsession with Paul Sheldon. The only joy in her life comes from the romance novels that she reads–a vicarious way to experience a full life–namely the

Misery series by Paul Sheldon. Essentially, she is the perfect storm of psychological and emotional disorders all wrapped up in a an unassuming citizen of a small Colorado town. She could very well be your neighbor or one of your social media followers. Perhaps she is YOUR No.1 fan.

Although screenwriter William Goldman adds in a subplot of the town’s sheriff investigating the disappearance of Paul Sheldon, which works very well for the film even though it was not in the novel, the story is about two characters (representing two sides of the same coin) trapped in a room together, locked in a psycho-social battle of wills. Ostensibly, this story features two characters whom represent the creative mind of Stephen King during his real addiction to alcohol. I mention this real-life time of darkness in King’s life not to glorify it because it helped inspire one of his greatest novels turned film (need I mention

Velvet Buzzsaw), but it helps us understand the depth and power of the character of Annie Wilkes. Both Sheldon and Wilkes work so well because they represent real life villains in the life of King. King’s real battle between his healthy mind and drug-induced state parallels Paul Sheldon’s battle for freedom with Annie Wilkes standing in his way. In a most brilliant fashion, the sadistic former nurse Annie is the manifestation of how controlling a drug addiction can be–how it makes the user a prisoner of one’s own mind and body. This subplot is strategically woven into the main action plot then delivered through the character development and character-driven scenes in the story.

Annie is not completely evil. Early on, she shows us that she cares about victims as she could not have known that it was Paul Sheldon that she was rescuing from the car crash. Being his No.1 fan, as soon as she saw him, she knew precisely who he was and therefore her obsessive nature takes over. There is a moment that encapsulates one of the film’s themes that is often overlooked. Prior to caring for Paul, Annie takes his attache full of manuscripts and tucks it under her arm thus symbolizing that Paul’s work is more important than Paul’s life. But that doesn’t confirm her psychopathic nature. Even upon the more formal introduction of Annie, she shows us that she cares about Paul’s recovery as she crudely splints his broken legs. Why not take him to the hospital? Well, because she is his No.1 fan and no one can take care of him the way she can. She goes on to shower Paul with accolades. Claims to have read his

Misery novels several times, even committing them to memory. Furthermore, she closely identifies with Misery Chastain (the series’ central character), so cares deeply what happens to her. Albeit being hospitalized in a stranger’s private residence is a little disconcerting, Paul grows to trust and even like Annie. He trusts her so much that he allows her to read the unpublished manuscript for the final

Misery novel. And this is where things take a turn for the worse, Paul’s hospital is about to turn into a prison ran by the sinister warden from hell.

During Annie’s rage over the offensive swearing in the unpublished manuscript, she spills the hot soup on Paul and we begin to see the signs of her mania, twisted morals, paranoia, and negative effects of OCD. Obviously, we learn more about her psychopathy as the scenes unfold, but in retrospect, we witness the signs in big bold letters from this moment on. But she doesn’t continually behave in such a neurotic manner. She oscillates back and forth. This oscillation is an important aspect to her character because it drives up the tension and suspense because we don’t know when or where to expect her dangerous behavior. There are moments that we anticipate a violent outburst, but then she fools us by not delivering. By the same token, there are moments that we don’t expect it, and she terrifies us. The character trait of Annie’s that makes her one of the most terrifying in the Blockbuster of horror is her lack of feeling. Everything she does, she rationalizes without regard for quality of life or humankind. The very definition of sociopath.

The psycho-social disorders affecting the behavior and psychology of Annie are never confirmed, and don’t need to be. We don’t need to know precisely why or what causes Annie to behave the way she does. Because if we fully understood her, she would cease to be as nightmare-inducing as she is. It’s important that Annie Wilkes remain a type of Boogeyman. However, we can gather from the film that she suffers from a form schizotypal personality disorder, OCD (which I’ve mentioned), and meets most of the criteria of borderline personality disorder. A trifecta of disorders that creates the monster that we encounter in the film. She copes with these disorders by executing numerous defensive mechanisms including denial, projection, rationalization, regression, fantasy, and more. Whereas we often talk about her psychopathy and sociopathy, we often neglect to recognize her highly intelligent mind. Too bad her intelligence isn’t matched by empathy and and human kindness. Her intellect is observed through how she anticipates Paul’s movements and knowing when he’s been out of his room. And an intelligent villain is the most dangerous and unpredictable of all.

Aside from her disorders, unpredictable behavior, and lack of empathy, attributes that can be found in other horror villains, she stands out because she is a women. It’s her feminism that enables her to stand out against similar villains such as Norman Bates, Jack Torrance, Buffalo Bill and others. When we typically think of female characters or women in general (and I realize I am over-generalizing), we think of someone whom is kind, hospitable, nurturing, passive, and empathetic. Annie subverts those notions in so many ways, many of which have been outlined in this analysis. She makes Joan Crawford from

Mommy Dearest look like Mrs. Brady. As out of control as Annie behaves, she is very much in control. She IS the one holding all the cards and calling the shots in this prison. While other characters (male or female) with similar disorders or backgrounds that parallel Annie’s have lost their minds, Annie knows precisely what she is doing, and is supremely strategic when she does it. We may be cheering when Paul finally kills her with the typewriter, in brilliant ironic fashion, but she is an incredibly strong female character who can hold her own, backs down to no one.

Not only is

Misery one of the top psychological horror films ever made, but Annie is a noteworthy female character in the horror genre. While the final girls get most of the attention when we talk Women in Horror, it’s important to not forget that horror has given us terrifying women as well. Whereas so often the most interesting villains (or characters of opposition) get to be played by men, this film would not be as powerful is the roles were gender swapped. The fact that this psychopath is a women makes her all the more disturbing. She crafts such overwhelming sense of dread that is more frightening because we aren’t used to female characters as the main villains. Kathy Bates was a perfect choice for this role, and she has gone on to play all kinds of roles but the horror community gets extra excited when she plays a horror role. While horror doesn’t often win awards at the Oscars, Kathy Bates won the Academy Award for an actress in a leading role for her work in

Misery.

Ryan teaches screenwriting and film studies at the

University of Tampa. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Interested in Ryan making a guest appearance on your podcast or contributing to your website? Send him a DM on Twitter or email him at RLTerry1@gmail.com! If you’re ever in Tampa or Orlando, feel free to catch a movie with or meet him in the theme parks!

Follow him on Twitter:

RLTerry1