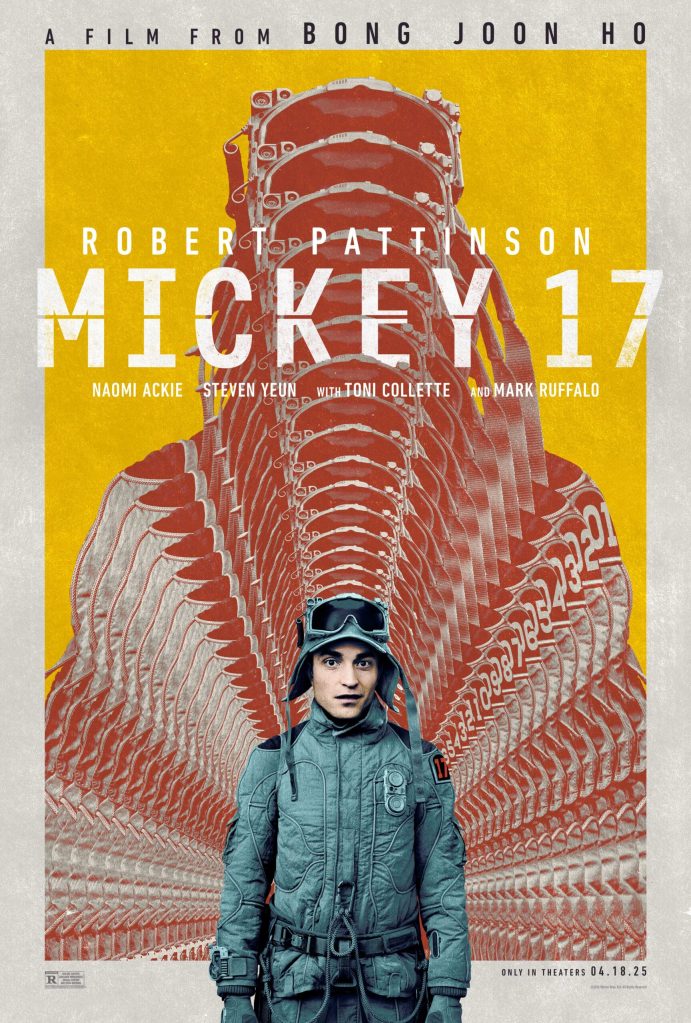

Ambitious but disjointed. Bong Joon-ho’s newest film Mickey 17 excels in technical achievement but the full impact of the story demonstrates greater concern for its satire, message, and world building than it does its plotting and structure. Blending multiple genre conventions, Joon-ho’s science-fiction, dark comedy begins with an intriguing premise underscores with existential questions, but ultimately doesn’t feel cohesive from beginning to end. Despite the exhaustive satire–which is entertaining at first–the film works excellently as a critique of the prolific mediation of society, obsession with the idea of self-made celebrity, and the camera fame. Additionally, it presents an exploration of humanity’s fixation on replication and surveillance. Perhaps the film doesn’t call out any particular app or platform, it certainly drives home the point that a monster can be created through obsession with one’s image, control, and manipulation of others.

Mickey Barnes (Robert Pattinson), a disposable employee, is sent on a human expedition to colonize the ice world Niflheim. After one iteration dies, a new body is regenerated with most of his memories intact.

Despite an intriguing premise, the narrative often succumbs to prolonged scenes and sequences, subplots that lack meaningful purpose, and over-explanation in come places whilst lack of purpose exists elsewhere. While the third act is strong and completely engaging, the first act is protracted and the second act is plagued by poor pacing brought on by a wandering direction. The protracted first act delays audience immersion into the core narrative. What would’ve served the plot better as a brief prologue, turns into most of the first act. Even though the film maintains a modicum of innovation and freshness, it struggles to sustain momentum, resulting in a clunky and disposable experience.

The film delivers a relatively strong performative dimension, which helps to keep the audience engaged–however weak the engagement–in the story. And, Robert Pattinson performance strikes a nice balance between nuanced and manic, which mimics the film’s darkly comedic tone. Between his and the other leading actors performances, collectively they add a rolling punchline to the monotony of many scenes and sequences in the film. Mark Ruffalo’s depiction of the authoritarian leader, Kenneth Marshall, is audacious and campy, but doesn’t take long for this performance to become exhaustive–a little goes a long way with Marshall. Playing Marshall’s wife is horror-fan favorite Toni Collette, and even her character overstays her welcome in most of the scenes in which she appears.

Both the plotting and character issues can be connected to the screenwriting, which lacks direction, purpose, and refinement. Mickey 17 is another example of a director with a great, even innovative movie idea, but should work with a screenwriter with a command of proper screenwriting conventions and mechanics to craft the story for the page, and eventually the screen. This issue is not unique to Joon-ho, but a recurring problem I find with many (if not most) writer-directors. Few directors can write as well as they direct; and the inverse is also true–few screenwriters can direct as well as they can write.

Mickey 17 serves as a critique of the mediation of society, wherein informative, entertaining, and surveilling media technologies devalue the individual resulting in individuality with dimension being reduced to a character or commodity to be traded and exploited for the sake of ratings and celebrity. Mickey’s existential crisis of repeatedly dying and being reprinted underscores the alienation experienced in a society that commodifies human existence. Furthermore, Keneth Marshall’s obsession with control and his self-made celebrity mirrors the obsession many have, in the real world, with their “celluloid” self–or more accurately today–their digital self.

Everything Marshall said or did was ran through an image consultant and production crew on how it would look on camera. Looking at the real world, each of those squared images on Instagram or vertical video on SnapChat or Tik Tok, only show an edited version of the subject–the framing and editing is specifically manipulated and articulated to shape the audience’s perception. While this is to be expected in motion pictures and television shows, many of these self-made celebrities and influencers on social media want the audience believe they are being authentic, when it’s all a facade. In this obsession with the camera and “framed” image, society is exchanging that which is real with a projected authenticity; furthermore, the lines between what which is real and that which is fictionalized (or augmented) are becoming increasingly blurred.

Bong Joon-ho’s Mickey 17 blends satire with science fiction but the film’s underdeveloped plot and uneven character portrayals prevent it from reaching the potential this film demonstrably had with the talent behind it.

Ryan is the general manager for 90.7 WKGC Public Media in Panama City and host of the public radio show ReelTalk about all things cinema. Additionally, he is the author of the upcoming film studies book titled Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror. After teaching film studies for over eight years at the University of Tampa, he transitioned from the classroom to public media. He is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Follow him on Twitter: RLTerry1 and LetterBoxd: RLTerry