From the Big Screen to the Smallest: The Oscars and the Final Lament for Cinema

In 1929, the Academy Awards were born alongside the consolidation of cinema as the defining art form of the twentieth century. The Oscars did not merely honor motion pictures; they sanctified the big screen as a cathedral of light where stories were projected larger than life, and where audiences gathered together in reverent silence to be transformed. Nearly a century later, the announcement that the Oscars will move to YouTube in 2029 feels less like an adaptation and more like a capitulation. It’s a moment of inflection that reads, unmistakably, as a eulogy.

Anyone who has followed my work on Twitter or my blog for any length of time knows that I effectively gave up on the Oscars years ago. Even so, this announcement demands cultural analysis and reflection on its deeper implications. One needn’t be a devoted viewer of the ceremony to recognize the ongoing erosion of cinema itself; disengagement does not preclude clear sight, and distance often sharpens it.

There is a morbid irony in a ceremony created to celebrate cinema’s grand scale choosing to live on the smallest screen possible. The Oscars migrating to YouTube is not simply a platform change; it is a symbolic reversal of values. The institution that once affirmed spectacle, patience, and collective experience now aligns itself with the very medium that played a decisive role in cinema’s metaphoric death—fragmented attention, algorithmic taste-making, and content flattened into disposable scrolls. What was once king has voluntarily donned the motley of the court jester.

For decades, the Oscars functioned as a kind of cultural mass. Even when ratings declined, the ceremony retained its claim to seriousness. It insisted—sometimes stubbornly—that movies mattered, that craft mattered, that the labor of hundreds could still culminate in something worthy of ritual. To move this rite to YouTube is to concede that cinema no longer warrants ceremony at all. It is now content, indistinguishable from reaction videos, vlogs, and monetized outrage. The awards will play not to the gods of light and shadow, but to the lowest common denominator of engagement.

This decision cannot be disentangled from the broader arc traced in the manuscript on which I am presently writing Are You Still Watching? Solving the Case of the Death of Cinema, which is my followup book to Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror releasing in October 2026. The internet did not merely change distribution; it reprogrammed desire. It replaced anticipation with immediacy, reverence with irony, and stars with personalities. The movie star—once a distant, luminous figure whose very remoteness fueled myth—has been rendered obsolete by constant access (except for you Tom Cruise–you are the last remaining movie star in the classical sense). When everyone is visible at all times, no one can remain larger than life. In this sense, the internet did not just kill the movie star; it dismantled the conditions required for stardom to exist.

The Golden Era understood something we have since forgotten: limitation creates meaning. The big screen mattered because it was rare. The theatrical experience mattered because it demanded surrender—of time, of attention, of comfort. The Oscars mattered because they crowned achievements that could not be reduced to metrics. Box office was discussed, but it did not dictate value. Craft, risk, and ambition still held currency. One cannot imagine the architects of Hollywood—those who built studios, nurtured stars, and believed in cinema as a national dream—viewing this moment without despair. The roll call of names etched into Oscar history now echoes like a rebuke.

The move to YouTube completes a long erosion. First came the shrinking theatrical window, then the dominance of streaming, then the rebranding of films as “content.” Each step was defended as pragmatic, inevitable, even democratic. Yet inevitability is often the language of surrender. By placing the Oscars on YouTube, the Academy signals that it no longer believes cinema deserves its own stage—literal or metaphorical. It accepts, finally, that movies are just another tile in the feed.

What makes this moment especially tragic is that it arrives cloaked in the rhetoric of accessibility. YouTube promises reach, youth, relevance. But to what end and at what cost? Cinema was never meant to be optimized for virality. Its power lay in duration, in immersion, in the audacity to ask audiences to sit still and feel deeply. An awards show on YouTube does not elevate cinema to the digital age; it drags cinema down to the logic of the internet, where attention is fleeting and meaning is provisional. That which is required by the desired algorithm will be that which dictates the ceremony and pageantry thereof.

And yet, this lament is not without pride. There was a time when this industry truly was an industry of dreams. When the Oscars crowned films that expanded the language of the medium. When a win could alter a career not through branding, but through trust—trust that audiences would follow artists into challenging territory. That history cannot be erased by an algorithm, even if it can be buried beneath one.

If the Oscars moving to YouTube does not signal the death of cinema, it is difficult to imagine what would. It is the final nail not because it kills something vibrant, but because it seals a coffin long prepared. What remains will continue to exist—films will still be made, awards will still be handed out—but the animating belief that cinema is a singular, communal art form has been surrendered.

The tragedy is not that the Oscars will stream on YouTube. The tragedy is that, in doing so, they admit they no longer know what they are mourning.

This loss of self-knowledge did not arrive overnight. Long before the platform shift, the ceremony began to erode its own authority through an increasing embrace of socio-political posturing by hosts and award recipients alike. What was once a night dedicated, however imperfectly, to the celebration of films, performances, and craft gradually transformed into a sequence of soapboxes. The Oscars mistook moral exhibitionism for relevance, and in doing so alienated a broad public that tuned in not for lectures, but for an affirmation that movies themselves still mattered.

This is not an argument against artists holding convictions, nor a denial that cinema has always intersected with politics. Rather, it is an indictment of a ceremony that lost the discipline to distinguish between art and advocacy. When acceptance speeches routinely overshadowed the work being honored, the implicit message was clear: the films were secondary. Viewers responded accordingly. Ratings declined not merely because of streaming competition, but because the ceremony no longer respected its own premise. Had hosts and winners remained anchored in the films—celebrating storytelling, performance, direction, and the collaborative miracle of production—the Oscars might have retained their standing as a cultural commons rather than a partisan spectacle.

In surrendering the focus on cinema itself, the Academy weakened the very case for its continued relevance.

Progress is often invoked as an unqualified good, but history suggests it is more accurately understood as an exchange—one that invariably involves loss. Sometimes that “loss” isn’t’ felt immediately, but there is inevitably some mild, moderate, or signifiant loss somewhere. Every cultural advance carries a cost, and the measure of true progress lies in whether what is gained outweighs what is surrendered. In the case of the Oscars, the pursuit of modernity, relevance, and moral signaling came at the expense of gravitas, neutrality, and shared cultural meaning. What was gained—momentary applause within narrow circles, fleeting relevance in the news cycle—proved insufficient compensation for what was lost: broad public trust, ceremonial dignity, and the sense that this night belonged to everyone who loved movies, not just those who spoke the loudest.

When institutions confuse change with improvement, they often wake to find that they have survived only in form, not in spirit.

Taken together, the Oscars decline follows a macabre logic—a ceremony founded to exalt scale, craft, and collective experience gradually surrendered its authority by de-centering movies themselves—first through moral grandstanding, then through technological appeasement, and finally through full assimilation into the internet’s attention economy. Each step was justified as necessary, inclusive, or inevitable. Yet the cumulative effect was corrosive. The Oscars did not lose relevance because audiences abandoned cinema; audiences abandoned the ceremony because it no longer stood for cinema as something distinct, demanding, and worthy of reverence.

What remains is a hollowed-out ritual, stripped of its gravitational pull, migrating to YouTube not as a bold reinvention but as an admission of defeat. The move completes the journey from cathedral to feed, from shared cultural moment to algorithmic afterthought. It confirms that the Academy has chosen survival at the cost of meaning—and in doing so, has preserved the shell of the institution while relinquishing its soul.

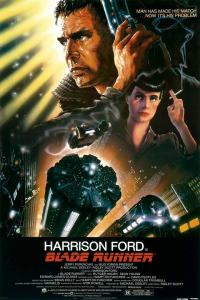

Gloria Swanson’s Norma Desmond, reflecting on the industry’s changing fortunes, once delivered an epitaph that now feels uncomfortably prophetic: “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.” A century after the birth of the Oscars, her words resonate with renewed clarity. Cinema did not shrink because audiences demanded less; it shrank because its stewards accepted less.

The Oscars’ migration to the smallest screen is not progress; it’s the final confirmation that something vast, communal, and luminous has been allowed to diminish, and that what replaced it was not worth the cost. A ceremony that no longer centered movies should not be surprised when audiences stopped gathering to watch it. The move to YouTube, then, feels less like a sudden betrayal and more like the logical endpoint of a long retreat: from celebration to commentary, from reverence to rhetoric, from a shared night at the movies to just another argument in the feed.

Ryan is the general manager for 90.7 WKGC Public Media and host of the show ReelTalk “where you can join the cinematic conversations frame by frame each week.” Additionally, he is the author of the upcoming film studies book titled Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror. After teaching film studies for over eight years at the University of Tampa, he transitioned from the classroom to public media. He is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Follow him on Twitter: RLTerry1 and LetterBoxd: RLTerry