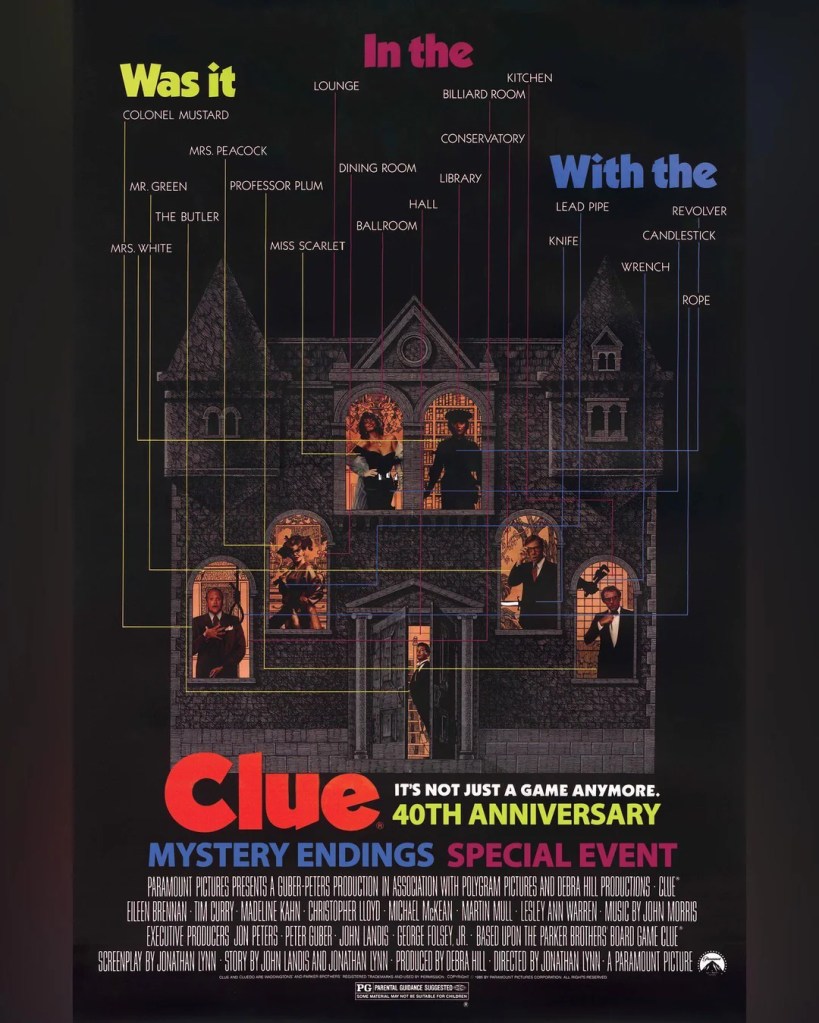

40 Years Later, It’s Still One of the Smartest Comedies Ever Made From One of the Dumbest Possible Premises.

Clue (1985) somehow caught lightning in a bottle, and has held onto it for four decade; this same lightning was then shaken and thrown against the silver screen in the most delightfully chaotic ways imaginable. Forty years later, this all-star murder mystery based on the classic boardgame remains sharper, funnier, and more lovingly crafted than most prestige comedies released today. What should have been a disposable novelty became a masterpiece of comedic architecture, tonal discipline, and ensemble chemistry. I first discovered it on VHS from my local public library, and even then I knew I had stumbled onto something special. My sister loves it as much as I do. It’s a movie that works on you—and then keeps working every time you revisit it.

For my show ReelTalk on WKGC Public Media this week, I invited returning guest and friend of the show, film critic Sean Boelman to join me in our celebration of Clue‘s 40th anniversary. You can listen to the show by clicking the appropriate link below. While my article captures the highlights of what Sean and I discuss, listening to the show after reading the article, you’ll have a much more robust experience!

At its core, Clue commits fully to three things most comedic mysteries never attempt at the same time: total absurdity, airtight plotting, and theatrical precision. Most films in the genre pick one lane—either slapstick, or clever mystery, or witty farce—but Clue weaves them together with an elegance that belies how frantic the movie feels moment to moment. Unlike many modern adaptations drowning in CGI, brand synergy, or self-aware winking, Clue treats its ludicrous premise with the sincere craftsmanship of an Agatha Christie play–yet–Clue’s apparatus is actually more closely related to the boardgame play than to the typical Christie literary apparatus. The humor is character-driven, rooted in rhythm, timing, and razor-sharp verbal dexterity. That sincerity, combined with its unhinged heart, is why the film remains timeless.

Much of Clue’s durability stems from how it uses language as a weapon. This is not a movie relying on boardgame nostalgia or shallow references; it is powered by dense wordplay, screwball pacing, and overlapping exchanges that feel plucked from a stage farce running at espresso speed. Every performer is asked to treat their lines with theatrical precision. The jokes arrive in layers, often stacked on top of each other, rewarding audiences who pay attention and enhancing the comedy with every rewatch. By grounding the absurdity in craft—rather than irony—the film avoids collapsing into randomness. It feels smart, not silly; intentional, not accidental. Humor this tightly constructed simply does not age.

Another reason the film works: it respects the genre it’s parodying. Clue doesn’t mock murder mysteries from a distance. It commits to the melodrama, the red herrings, the stakes—even as it gleefully skewers them. Parody only works when sincerity lies beneath the joke. Modern adaptations often fail because they either drown in self-awareness or cling to seriousness so tightly the comedy feels bolted on. Clue threads the needle by honoring the mechanics of a whodunit while joyfully stretching them to the breaking point. It loves the sandbox it’s playing in, and the audience can feel that affection.

Of course, the film’s most unforgettable asset is its ensemble cast, which may be one of the best comedic troupes ever assembled on screen. These are character actors trained in theater, sketch, and improv—who understand timing and ensemble harmony better than any star-studded ensemble today. Tim Curry’s manic precision, Madeline Kahn’s volcanic eccentricity, Michael McKean’s brilliant awkwardness, Lesley Ann Warren’s slinky aloofness—every actor is distinct, yet completely in tune with the film’s wavelength. No one competes for the spotlight; instead, every moment becomes a relay race of comedic energy. Modern ensemble films often feel like stitched-together “bits.” Clue feels alive, reactive, and musical. It is an ensemble in the purest sense.

And then, of course, there are the multiple endings—a theatrical gamble so audacious it could have sunk the film entirely. Instead, it became an iconic part of its identity. In 1985, you never knew which ending you’d get in theaters, a cheeky nod to the board game’s replayability. Instead of feeling gimmicky, it felt organic to the world of the film—a natural extension of its playful tone and farcical structure. Today, a studio would almost certainly turn the idea into a marketing ploy or streaming bonus feature, but in Clue, the endings are crafted with sincerity and precision, not cynicism. They’re not content strategy; they’re punchlines.

The film’s simplicity is another key to its longevity. Where modern game adaptations inflate themselves into lore-heavy franchises, Clue keeps everything contained in one house with one group of increasingly frantic characters. The mansion becomes a pressure cooker where personality collisions become the main spectacle. No elaborate world-building, no digital spectacle—just smart writing, sharp performances, and a commitment to letting the humor build naturally. The film’s scale is its strength.

Would Clue still find an audience today? Absolutely—although probably through a different path. Theatrical comedy has become a rare species, and a film this verbally dense might struggle to secure screen space. But word of mouth would spread like wildfire, and social media would turn its most quotable lines into instant memes. If anything, its intelligence, compact scope, and genuine ensemble work would feel refreshingly rebellious in today’s IP-heavy landscape.

What ultimately makes Clue endlessly rewatchable—more than contemporaries like Knives Out—is that it’s a comedy first and a mystery second. The joy doesn’t hinge on solving the puzzle; it hinges on watching these characters unravel in the most glorious fashion. Puzzles fade with familiarity. Brilliant performances only deepen. The more you watch Clue, the funnier it becomes.

So what is Clue’s greatest legacy? It proved something rare: that a film can be wildly silly and intellectually sharp at the same time. It’s a miracle of tonal balance, ensemble synchronicity, and writerly discipline. A movie that treats its audience with respect even as it descends into delightful chaos. A movie that should have been forgotten…yet became unforgettable.

Forty years later, Clue remains the gold standard—not because it adapts a board game faithfully, but because it transcends one. It is lightning in a bottle. And every time we open that bottle, the spark still flies.

Ryan is the general manager for 90.7 WKGC Public Media and host of the show ReelTalk “where you can join the cinematic conversations frame by frame each week.” Additionally, he is the author of the upcoming film studies book titled Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror. After teaching film studies for over eight years at the University of Tampa, he transitioned from the classroom to public media. He is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Follow him on Twitter: RLTerry1 and LetterBoxd: RLTerry