A very lose adaptation.

Is it a bold, thoughtful reinterpretation of a literary classic—or a grotesquely self-indulgent fever dream? Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights positions itself squarely at the intersection of gothic romance and modern sensibility, daring to reimagine Emily Brontë’s tempestuous novel for contemporary audiences. The question is not whether Fennell has vision—she undeniably does—but whether that vision honors Brontë’s architecture or merely rearranges it to suit her own aesthetic impulses.

Tragedy strikes when Heathcliff falls in love with Catherine Earnshaw, a woman from a wealthy family in 18th-century England. What follows, in Brontë’s telling, is a slow-burning study of pride, cruelty, class, and decay.

Let us begin where praise is due. Emerald Fennell is undeniably a visionary director. Her eye for composition, color, texture, and environmental immersion is extraordinary. Every frame feels curated—shadow and candlelight carefully balanced, fabrics heavy with implication, the moors rendered both seductive and foreboding. The costuming and production design are exquisite, nearly flawless in execution. If one were evaluating this film purely as visual art, it would stand among the most striking adaptations of Brontë ever mounted. There is a neo-gothic confidence in its aesthetic—modern, tactile, and immersive.

Unfortunately, that same discipline is absent from the screenplay.

Fennell the director and Fennell the writer feel like two different artists. Subtlety is sacrificed in favor of blunt-force reinterpretation. When Fennell adheres closely to Brontë’s plotting, the film works. When she strays—and she strays often—the adaptation buckles under the weight of unnecessary revisionism.

The most egregious example is the character assassination of Catherine’s father. In both the novel and the 1939 William Wyler adaptation, he is a kindly, stabilizing force—the glue that holds the family together. It is only upon his death that his biological son, Hindley, descends into cruelty and degradation, transforming Heathcliff from adopted son to servant in a perverse Cinderella inversion. Fennell eliminates Hindley altogether, redistributing his vices—gambling, drunkenness, cruelty—onto the father himself, rendering him a monstrous, bigoted drunk from the outset. This is not reinterpretation; it is structural sabotage.

By corrupting the father from the beginning, the narrative loses its axis of decay. And decay is central to Wuthering Heights. The estate should mirror the relationships within it—beautiful at first, falling gradually into ruin as love curdles into vengeance. Yet Fennell presents Wuthering Heights as decrepit from the outset. If everything is already broken, there is no meaningful deterioration to witness. The symbolism collapses before it can resonate.

Isabella Linton suffers a similar flattening. In Brontë’s novel and prior adaptations, she possesses dimension, agency, and tragic complexity. Here, she is comparatively inert, stripped of the inner life that once made her more than a narrative device. Again, when Fennell stays close to Brontë, the film steadies itself. When she diverges, the narrative weakens.

Pacing further undermines the film’s impact. What could have been told effectively in an hour and forty-five minutes stretches to two hours and fifteen, with a protracted second act that tests even patient viewers. Entire opening sequences could be excised without loss, and substantial portions of the middle tightened considerably. One feels the absence of editorial restraint—the checks and balances that a separate, more disciplined screenwriter might have imposed.

And yet, there are cinematic pleasures here.

While the narrative falters, the film’s visual architecture is nothing short of extraordinary. Production design, cinematography, and costuming operate in near-perfect harmony, creating a world deeply rooted in Gothic romance yet unmistakably filtered through contemporary sensibilities. The estate’s textures—weathered wood, cold stone, candlelit interiors—create a tactile atmosphere that is immersive and deliberate. The color palette oscillates between muted earth tones and saturated bursts of crimson and shadow, suggesting emotional volatility beneath composure.

The costuming deserves particular recognition. Fennell understands silhouette and line as psychological tools. Structured bodices, layered fabrics, and stark contrasts in texture mirror emotional rigidity and suppressed desire. There is a modern sharpness in the tailoring—a recalibration that prevents the film from feeling museum-bound. This is Gothic romance rendered through a contemporary lens without collapsing into gimmickry.

The cinematography further elevates the material. Light and shadow are deployed not merely for aesthetic pleasure but for emotional suggestion. Faces emerge from darkness as though haunted by memory; candlelight flickers against stone walls like unstable devotion. Fennell’s compositional instincts are impeccable—symmetry fractured at key moments, framing that isolates characters even when they occupy the same space. Visually, this Wuthering Heights breathes.

Fennell’s restraint also deserves applause. After the provocative spectacle of Saltburn—and the social media speculation that followed—many anticipated a sexually explicit interpretation of Brontë. Instead, this adaptation is comparatively restrained. Passion is implied more often than shown. Edginess exists, yes—but it is measured, not gratuitous. Ironically, this restraint underscores her discipline as a director even while her writing falters.

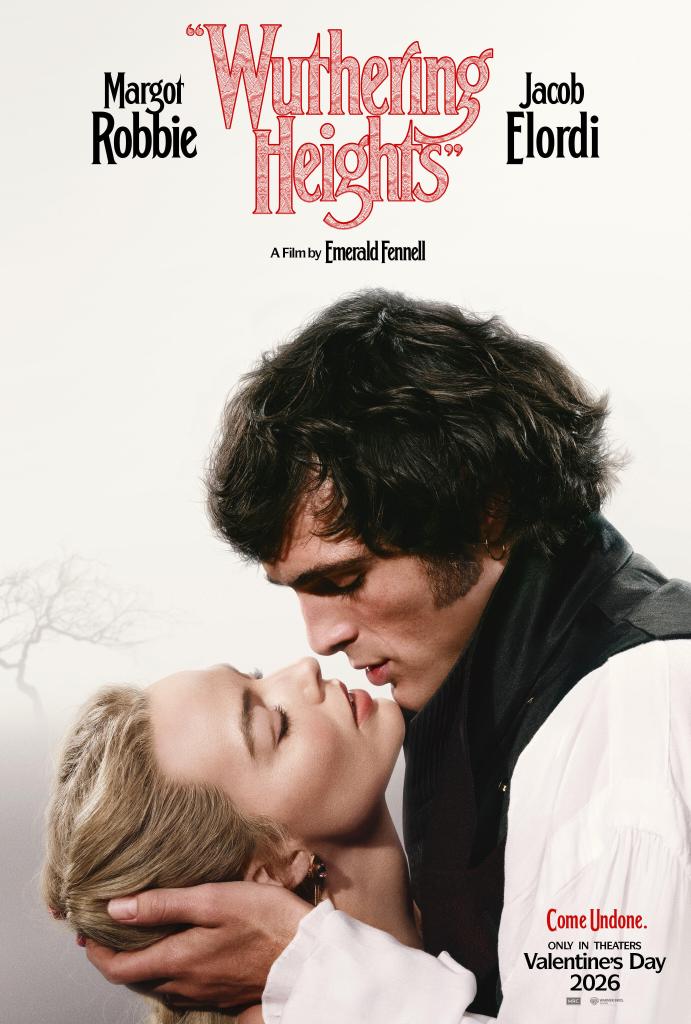

Performatively, the film is strong. Robbie and Elordi deliver committed, emotionally grounded performances, leaning into the operatic intensity of the material without tipping into parody. Hong Chau, as Nelly, provides a compelling presence—observant, restrained, and quietly anchoring the emotional chaos around her. The cast frequently elevates what the script undermines.

There are even moments—brief, surprising—that are genuinely funny. Fennell understands tonal modulation, allowing dry humor to flicker through the gloom like shafts of unexpected light.

Ultimately, 2026’s Wuthering Heights is immersive and visually arresting but narratively anemic. It demonstrates how essential the collaborative checks and balances of cinema truly are. A more disciplined screenwriter paired with Fennell’s formidable directorial skill could produce something extraordinary. Instead, we are left with an adaptation that is imaginative, occasionally exhilarating—and unlikely to command a rewatch.

It is not without merit. But it mistakes alteration for insight, excess for depth, and provocation for revelation. And for a story as enduring as Brontë’s, that is a costly miscalculation.

Ryan is the general manager for 90.7 WKGC Public Media and host of the show ReelTalk “where you can join the cinematic conversations frame by frame each week.” Additionally, he is the author of the upcoming film studies book titled Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror. After teaching film studies for over eight years at the University of Tampa, he transitioned from the classroom to public media. He is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Follow him on Twitter: RLTerry1 and LetterBoxd: RLTerry