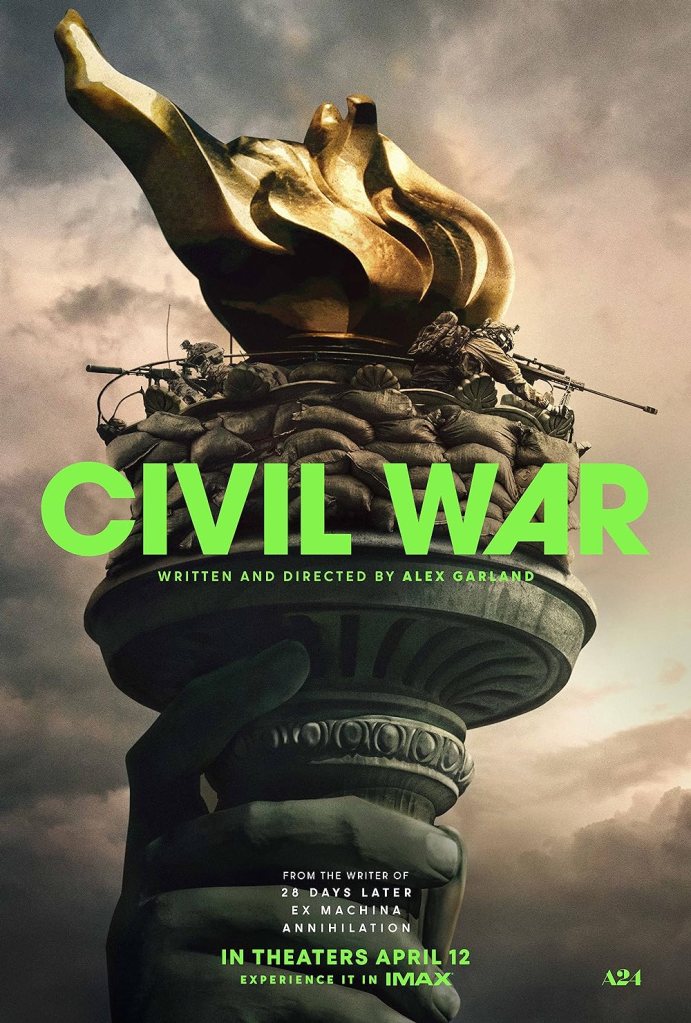

A gripping, thought-provoking motion picture about the power and cost of capturing the human experience in a single frame during war. While it would be easy to describe Alex Garland’s Civil War as a thoughtful, if not painful, graphic warning of what happens when society is completely deconstructed and humanity is lost, this film is actually about the power of storytelling through a single frame. Specifically, the state of what remains of humanity and the cost thereof amidst war. Not for the faint of heart, this film takes you only where imbedded journalists have been during a war, complete with all the death and destruction. The film reminds us of the human cost on the battlefield, in the neighborhood, and those that are capturing the images that will tell the story of societies darkest days.

In a dystopian future America, a team of military-embedded journalists races against time to reach Washington, D.C., before rebel factions descend upon the White House.

A picture is worth a thousand words, or so we hold true, but a picture can come at great cost, particularly during wartimes. Instead of focussing on the backstory or who is fighting for whom and for what principles, Garland uses the apparatus of a dystopian warn-torn United States to explore the human dimension and cost of a polarizing, grizzly domestic war. And he does this through a group of imbedded journalists played by Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Maura, Cailee Spaney, and Stephen McKinley Henderson. Together, they face certain death as they strive to cover the war and reach the President for a one-on-one interview.

We aren’t given enough information about the reason for the Western Front (California+Texas) and Florida Alliance secession from the rest of the country, but that’s because Garland wants us to focus on a different story, the human story told through the power of a single frame and the lives that bring these photos before our eyes. Perhaps you’ve never thought of how these photos get from the battlefield to online and traditional magazines and newspapers, but you’ll think twice the next time you are viewing photographs from current or past wars.

But it isn’t simply a motion picture depicting the difficulties in working as a wartime imbedded journalist–that is incidental–this is a picture of the human lives on the battlefield and the places seemingly removed from the atrocities of war. We seldom think of all the different human reactions to war, and this film brings us face to face with those that are fighting for their respective causes, those documenting the various campaigns, and those that go about their daily lives as though the country isn’t ripping apart at the seems a few hundred miles away. Garland doesn’t offer any particular slant, neither does he steer the audience in agreement or disagreement with any faction involved in the war; rather, he crafts a mosaic, if you will, of a collection of metaphoric still images that capture each type of reaction to the war.

I often talk about the emotive difference between film and digital in my classes, and this film is a great example of that argument. It’s the argument that film is superior to digital because with film, there is a tangible relationship between the filmmaker and the film stock, and by extension, a relationship is developed between the editor and film stock. We particularly witness this relationship in Civil War between Jessie (Spaney) and her classic Nikon SLR (film) camera. Whether as depicted in this movie or in real life, there is far more value placed on and discernment in using film to capture people and events, because the photographer/filmmaker is limited to the number on frames on each roll/reel. Therefore, the photos won’t be of just anything, the artist is only going to take a photo that has meaning. Granted, the keeper may still be 1/30, but each was taken with explicit intent, creating immense value in each still frame.

Even after the shutter has opened and closed, imprinting the image on the 35mm frame, the relationship continues through the development process because the developer sends the film through a chemical process that reveals the full spectrum of light–something tangible, that the developed can see, touch, and feel. Digital cannot capture the full spectrum of light the way film can: one is a replicated process that actually cuts off the whitest of whites and blackest of blacks, whilst the other is a chemical process that captures the full range and spectrum of light as imprinted on the film cell. Film photography (or cinematography) creates an emotive dimension between the artist and image, there is a tangible relationship, so everything is done with immense care, consideration, and discernment.

Why is any of this important in discussing Alex Garland’s Civil War? Because to gain the full appreciation of the story he is telling, it is imperative that we understand the relationship between the photojournalist and tragic, devastating events in which they are working to capture the human dimension behind the atrocities of war. Neither Jessie nor Lee (Dunst) will take photos of just anything, every move is thoughtful, the people and events being captured by their respective cameras carry meaning, they carry the human story. That story is made up of those fighting for the Western Front, Florida Alliance (which we don’t see in the movie), or what’s left of the (former) United States’ armed forces.

Beyond what emerges as the main story, Garland’s film does contain a graphic warning of a possible future in which the United States becomes embroiled in domestic warfare (civil war) due to whatever the reasons were that lead to the secession by California, Texas, and Florida (the three most populous states, by the way). It’s to the film’s credit that Garland does leave the backstory vague, as it’s less important what led to this point, but rather the importance is found in the reactions to the war. Both sides of this war are being fought by those that believe they are right, and will fight for the principles in which they believe. The problem isn’t simply the divergence of opinion and belief as it is in the complete disregard or sacrifice of humanity in exchange for a manmade or arbitrary identity.

This is witnessed in an exchange between our journalists and a group of paramilitary civilians, led by Jesse Plemons). Our journalists state they are American journalists, and Plemons’ character reacts by demanding to know what kind of American. This represents those that discriminate or hold prejudice against those that don’t look or sound like they are originally from the United States. In his mind, being from the United States looks and sounds like a particular type, and if one does not fit into that type, then they are not welcomed and ultimately expendable.

Other reactions to the war are also witnessed by our journalists. Such as the lack of reaction to that which is tearing the country to shreds. On their way from New York City to Washington, D.C., our central characters stop in a West Virginia town that is seemingly removed from the war. When the citizens of this town are asked how can they behave as though a few hundred miles away that the very foundations of the country are being shattered, the town reacts in apathy to the war. They are certainly knowledgeable that there is a war, but they choose to stay out of it. Just as the front lines are a reaction to war, this too is a reaction that bares consideration. Garland leaves it up to each audience member where they fall along the full spectrum of the human dimension in war.

In addition to the writing, directing, and technical achievement demonstrated in the film, the performative dimension is outstanding. The genuine reactions to and emotions on display are dripping with authenticity. You will feel what these actors’ characters are feeling throughout the movie. And not just the gut-wrenching parts, the strategically placed moments of humor will stir your soul as well.

Garland crafts a motion picture that serves as cautionary tale of what happens when we stop thinking about one another as unique individuals, as children of God, and instead treat those that are different in some way as a threat to our very existence. What happens when we care more about someone’s identity (with whatever the ideal or principle) than we do about them as a person. There is a time to defend that in which one believes or when one’s life is in danger, but left unchecked, that defense can turn into an offense due to primal fears, anxieties, obsession, and selfishness. Perhaps this film will serve as a reminder of what can happen when we stop treating one another with respect as fellow humans (as fellow Americans) and instead merely treat one another as threats to our very existence. Treatment with respect and dignity does not equate to endorsement or agreement, but it does leave an opportunity to change open. We’ve seen throughout history that there is sometimes a cause for war, but it should always be the last resort.

Often times, I am negatively critical of the writing in the film’s A24 produces or distributes, because I find many of these films are poorly written; however, this film demonstrates the power of acknowledging storytelling/screenwriting conventions and guidelines. Why? Because they work! At first I was wondering why with such a fantastically written screenplay was the realization missing at the end. Then I realized that it is there in character, plot, and in myself. You’ll just have to watch the film to fully understand that which I am attempting to describe without giving away any spoilers.

Garland’s Civil War is unlike anything I expected. I expected a movie dripping with overt socio-political ideology and commentary, but what I got was an incredibly thoughtful motion picture about the human dimension of war, particularly a domestic war between the states. Garland does not hold back on the violence, so those with PTSD from war or uncomfortable with violent movies should be cautioned before watching this film.

Ryan teaches Film Studies and Screenwriting at the University of Tampa and is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Interested in Ryan making a guest appearance on your podcast or contributing to your website? Send him a DM on Twitter. If you’re ever in Tampa or Orlando, feel free to catch a movie with him.