A cautionary tale of when YouTubers confuse content with cinema.

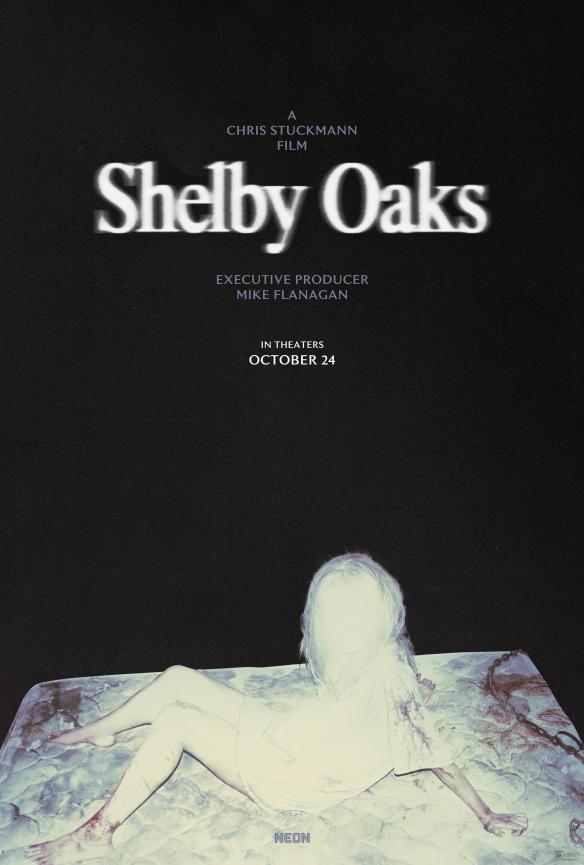

Chris Stuckmann’s Shelby Oaks arrives with all the makings of a breakthrough: (1) it’s one of the most successful Kickstarter-funded indie films ever, and (2) it’s directed by one of YouTube’s most popular influencer-critics. In fact, I’ve used some of his videos in my own classroom—good material: informative, engaging, and accessible for budding cinephiles. But therein lies the rub: informative and engaging does not a motion picture make. The premise, though, is undeniably intriguing—a reimagining of familiar horror tropes with contemporary urgency. Stuckmann delivers a film that has the bones of something potent—think The Blair Witch Project meets Rosemary’s Baby: paranoia, obsession, and the horror of the unseen, all wrapped in a missing-person mystery and topped with a bow of supernatural dread.

Shelby Oaks is about Mia’s search for her long-lost sister and paranormal investigator Riley becomes an obsession when she realizes an event from her past may have opened the door to something far more sinister than she could have ever imagined.

Like many contemporary filmmakers–particularly those that got their start on YouTube–Shelby Oaks excels in technical achievement and marketing. The cinematography is confident and atmospheric, drenched in moody lighting that evokes gothic horror. There is little doubt that Stuckmann clearly understands shot composition, pacing within the frame, even editing in-camera and the importance of visual tone. All the technical elements are quite impressive for a debut feature. And if all a motion picture was–was the visual elements–it’d be easy to admire. But it isn’t. Even Hitchcock knew that. Which is why Hitch never wrote his own screenplays–he generated the idea, even outlined entire scenes and sequences–but he knew that he needed to work with a screenwriter, that understood the material, in order to fully realize his movie idea for the screen. What is greatly lacking in contemporary cinema is an understanding of what makes a great story–plot structure, mechanics, and the emotional substructure.

But Shelby Oaks falters where too many YouTube-born filmmakers stumble—storytelling. Shelby Oaks has a great idea for a movie, but not a fully realized narrative. At its core, the narrative never builds sufficient momentum. Why? Simple–because there’s no real opposition. “Evil,” in the abstract, isn’t conflict. Opposition must manifest into something tangible between the character and his or her external goal, whether that’s a person, a system, or her own inner demons. For all the supernatural activity in the film, there never truly emerges a character of opposition. The result is a macabre mystery that depicts scenes and sequences wherein Mia’s pursuit unfolds, but without the benefit of a tangible sense of escalation or even revelation. Shelby Oaks is more of a proof of concept rather than a complete story.

Stuckmann, for all his film knowledge, seems more comfortable replicating tone and texture than constructing narrative architecture. His background in reviewing movies gives him an eye for what looks right—but not yet the discipline to shape what feels right. He understands what sells, what gets views, and even genre conventions. But sadly, none of the characters, including Mia, possess real dimension or agency. She and the rest of the characters are vehicles for mood rather than emotional engagement.

What works on YouTube—enthusiasm, charisma, and technical dissection—doesn’t automatically translate to cinema. His channel reveals a deep love of horror and a commendable understanding of its visual language, yet Shelby Oaks exposes the gap between appreciating a genre and authoring it. The film lacks what isn’t needed in (and can even get in the way of) YouTube content: storytelling mechanics, structure, and the discipline of narrative design. It’s one thing to analyze story beats; it’s another to build them, to shape character arcs, rhythm, and tension through the grammar of storytelling rather than the syntax of spectacle. Often, YouTube videos have great hooks, but they lack the narrative substance behind the hook.

What’s most frustrating is how close Shelby Oaks comes to working. The concept is rich, and the craftsmanship is undeniably strong. Stuckmann clearly loves cinema, and there’s passion behind every frame. But cinema isn’t content creation—it’s storytelling. And storytelling requires more than aesthetic confidence; it demands structure, development, and resolution.

The YouTube garden is flourishing with emerging directors, cinematographers, and editors—talented creators who’ve mastered the language of cameras, lighting, and cutting for attention. But what it’s not producing are writers. The art—and science—of writing seems to be withering in the age of influencer cinema. Many creators know how to make something look good but not why it should matter. Storytelling requires patience, discipline, and a willingness to think beyond the thumbnail and algorithm. In a culture where speed and spectacle drive engagement, screenwriting—the slow, deliberate architecture of character, conflict, and change—feels almost antiquated. And yet, it remains the soul of cinema. Without writers, we get films that resemble content: sleek, competent, and hollow.

Shelby Oaks stands as a cautionary tale of when YouTubers confuse content with cinema. Furthermore, this movie is an example of the hollowness of contemporary cinema, how cinema is feeling more and more disposable as the months and years pass the silver screen. The tools are there, the ambition is there, but without mastery of story, all that remains are haunting images in search of a heartbeat.

Ryan is the general manager for 90.7 WKGC Public Media in Panama City and host of the public radio show ReelTalk “where you can join the cinematic conversations frame by frame each week.” Additionally, he is the author of the upcoming film studies book titled Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror. After teaching film studies for over eight years at the University of Tampa, he transitioned from the classroom to public media. He is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Follow him on Twitter: RLTerry1 and LetterBoxd: RLTerry