An intoxicating and provocative neo-gothic film that is tonally all over the place. Heathers meets Cruel Intentions meets Flashdance(?) in a film that is incredibly stylistic but lacks any lasting entertainment value, except for the very end. Emerald Fennel (Promising Young Woman) delivers a sensory explosion critique on the facades we project through a story of the shifting balances of power, obsession, and deception. Is it a dark comedy? Is it a psychological thriller? Answer: it’s both and neither, and to that end, it’s potential for motion picture excellence is hampered. The tone of the film is incredibly uneven; and not one single character is likable. Saltburn presented many opportunities for effective, intentional camp, but chose to go the more serious route and play it straight.

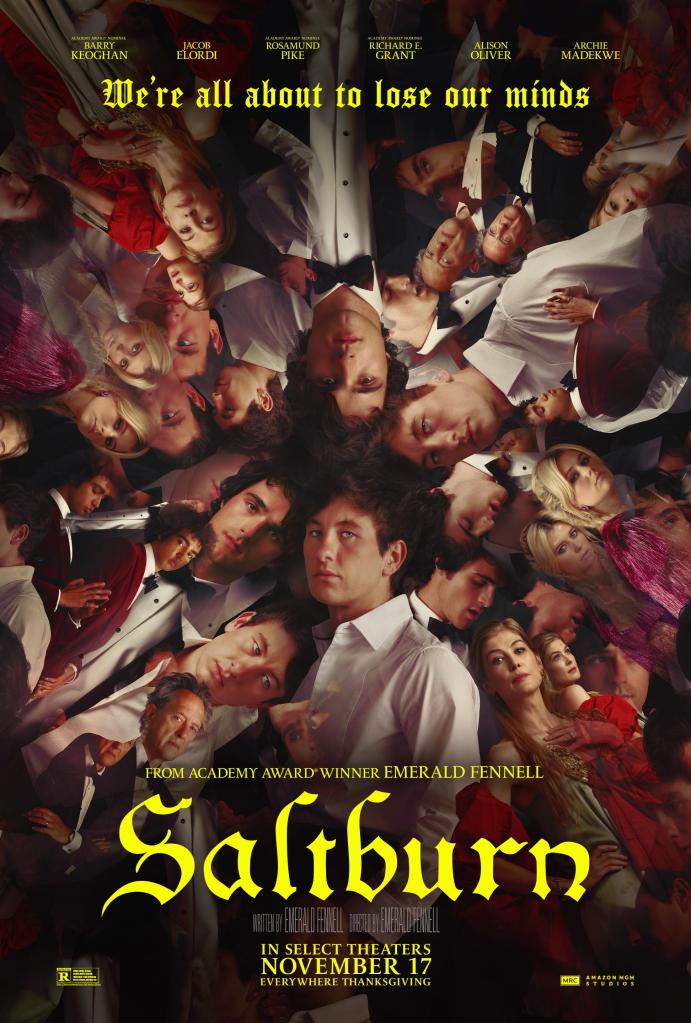

Oliver (Barry Keoghan), a freshman at Oxford, is invited by classmate Felix’s (Jacob Elordi) family’s country estate for an exciting summer, but things are not what they seem and soon the fantastical estate falls victim to deception and manipulation.

The aforementioned movie examples in the opening paragraph each feature an aspect of this film; but each of those three examples offers a great deal more in entertainment value, not to mention lasting impact upon popular culture. Even though the central character’s external goal doesn’t become clear until the end, it is a thoughtfully plotted film that you wish you had enjoyed more in order to watch it again. However, the very last scene of the film is one that takes direct inspiration from Flashdance, and will be what is likely talked about for years to come. Too bad the rest of the film wasn’t as fun and entertaining as the final scene. Saltburn is neither an uplifting story nor is it a cautionary tale; it’s uncomfortably somewhere in the middle.

Clearly Emerald Fennell has a fantastic eye for shot composition and a demonstrable talent for crafting environments that stimulate the senses and emote. And that is to be commended. Few directors have a gift for creating and capturing settings and environments that communicate a discernible mood, tone, or emotion. We witness this in German Expressionism, which is at the root of gothic and many horror films. No surprise then that this film is incredibly neo-gothic in story and setting. Saltburn embodies uses both the technical and performative dimensions of the mise-en-scene to challenge audience perceptions; moreover, gothic films concern themselves with sexuality and audience response thereto. The collective imagery in this film generate a kind of spectacle for the audience to draw us into a heightened state of unease or fear. Fennell’s Saltburn is an exemplary motion picture for the art of drawing the audience into the world inhabited by the characters, and beckons you to join them.

Sounds great, right? If there were any characters worth caring about, then Saltburn could indeed be the masterpiece that many have claimed it to be. Fennell nailed the neo-gothic aesthetic and further stimulated our senses with the film’s intoxicating sexuality, but there isn’t a single character that you care enough about whether they live or die. These characters will both attract and repulse you, but more repulsive than attractive. No doubt that Oliver will become the stuff of erotic fan fiction and dreams, but even he isn’t likable in the end. And when delivering a melodrama about facades, pretenses, obsession, and deception, whether the film ends on a high or low note, there should always be at least one character the audience can root for, can truly care whether they live or die.

The story of Saltburn is inspired by the narratives of both Heathers and Cruel Intentions. And I don’t mention this to in any way suggest that Saltburn is derivative–it’s not–but to draw parallels to similar films. While I feel that both of these movies are much more rewatchable than Saltburn, if you like those two movies, you will likely enjoy it, even if you watch it one time. Where Heathers and Cruel Intentions succeed and Saltburn fails is in the entertainment value and tonal consistency. It’s as if Fennell was so concerned with provoking and sensually stimulating the audience that she forgot that the film should still be entertaining. Just because a film contains dark comedy or scathing social commentary doesn’t mean that it’s excused from providing entertainment for the audience.

What I will remember most is the ending of the film, which I cannot talk much about because of spoilers; however, I know that Fennell must love Flashdance because the final scene of the film is clearly inspired by the audition and triumph scene when Alex (and the dancers portraying her, haha) dance to Flashdance…What a Feeling! by the late Irene Cara. Even though we love Flashdance, we all know the plot is honestly not very good, but what saves the movie that literally defined the music, dance, and fashion of the 1980s is the uplifting, inspirational story and the high degree of entertainment value, not to mention one of the best jukebox soundtracks of all time (it won both an Oscar and Grammy for best original song).

Even though the tone may be inconsistent and characters unlikeable, the film certainly delivers on immersive atmosphere and a spider-like web of deception and manipulation with a great cast.

Ryan teaches Film Studies and Screenwriting at the University of Tampa and is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Interested in Ryan making a guest appearance on your podcast or contributing to your website? Send him a DM on Twitter. If you’re ever in Tampa or Orlando, feel free to catch a movie with him.