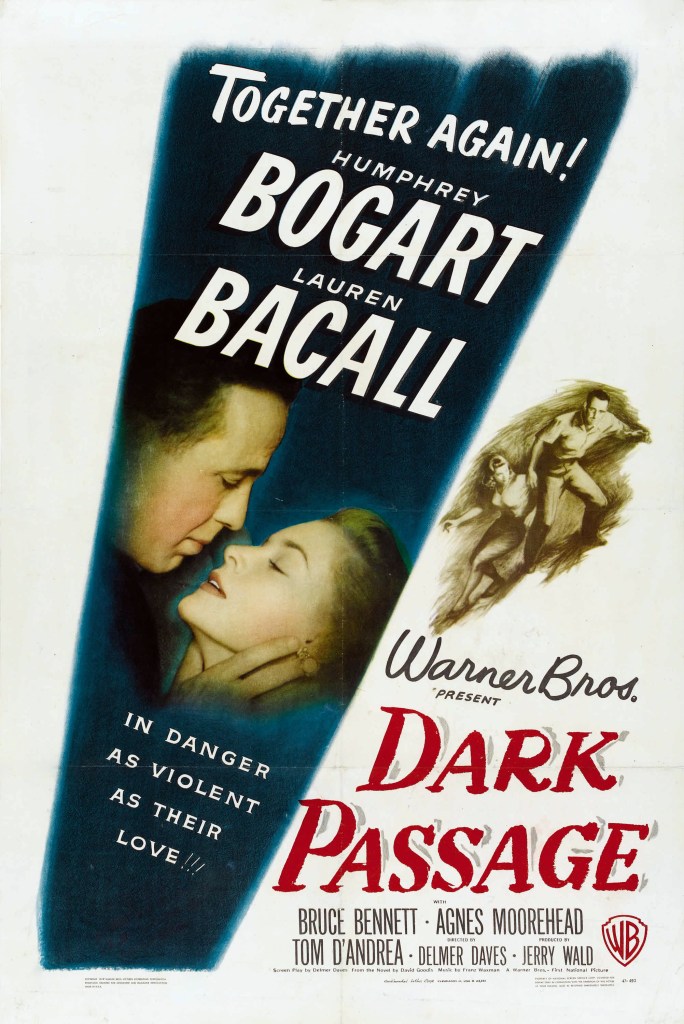

Spectacular and immersive! Dark Passage is the outstanding Bogie-Bacall film noir that you’ve likely never seen or even heard of, but you’ll want to change that. From beginning to end, this motion picture never ceases to draw you into its mysterious, seductive atmosphere. Bogie delivers a noteworthy performance through his dynamic facial expressions and body language, but it’s Bacall that steals the show through her sultry, smart, and sensational screen presence and performance. Dark Passage simultaneously checks all the film noir boxes whilst delivering something fresh and exciting.

Vincent Parry (Bogart) has just escaped from prison after being locked up for a crime he did not commit–murdering his wife. Vincent finds that his face is betraying him, literally, so he finds a plastic surgeon to give him new features. After getting a ride out of town from a stranger, Vincent crosses paths with Irene Jansen (Lauren Bacall), who believes in his innocence and helps him unravel the mystery surrounding his wife’s murder.

The most striking production element of Dark Passage is its innovative use of motivated camera framing and movement, which provides a unique and immersive perspective for the audience. By presenting the action from Vincent’s point of view (POV), the audience is drawn into his experiences and emotions, creating a sense of empathy and connection with the character. This technique adds a layer of suspense and tension to the film, as the audience is kept in the dark about Vincent’s true identity until later in the story. While POV camera is commonplace today, in the 1940s it was almost unheard of, which may have contributed to the reception of the film. But, if you’re searching for an excellent example of emotive POV camera, then definitely add this movie to your watch list.

Thematically, the film concerns itself with exploring concepts such as identity, justice, and redemption. Vincent’s transformation through plastic surgery raises questions about the nature of identity and whether changing one’s appearance can truly alter who they are on psychological, physiological, and emotional levels. As Vincent searches for his late wife’s real killer in order to clear his name, he grapples with issues of morality and the quest for justice in a corrupt world.

Underscoring the aforementioned themes is the compelling and complex relationship between Vincent and Irene. Irene’s unwavering belief in Vincent’s innocence provides him with hope and motivation to continue his search for the truth. Their growing bond adds depth to the story and serves as a contrast to the darker elements of the plot, because of the humor generated by their conflicting personalities. Film noir isn’t characterized merely by grayscale images (commonly referred to as black and white), but specifically the high contrast between light and dark. The high contrast isn’t only communicated visually, but is communicated thematically as well. In Dark Passage, the humor in Vincent and Irene’s relationship is the light to the film’s dark elements.

Lauren Bacall delivers a captivating performance as the determined Irene Jansen, Bacall’s portrayal of Irene is both alluring and sympathetic, adding depth to the character and serving as a crucial counterpart to Humphrey Bogart’s Vincent. Bacall’s performance exudes confidence and intelligence, traits that are essential for Irene as she navigates the morally ambiguous world of the film noir genre.

Perhaps the very definition and embodiment of femme fatale, Bacall communicates strength and cunning whilst never at the expense of sensuality and seduction. Moreover, she simultaneously conveys both fortitude and vulnerability beneath her character’s poised exterior. Bacall authentically portrays a relatable human dimension, allowing the audience to empathize with Irene’s plight and unwavering support for Vincent.

Furthermore, Bacall brings a sense of sophistication and glamour to the role, seamlessly fitting into the noir aesthetic. Her distinctive voice and sultry demeanor add to Irene’s allure, making her a memorable presence in every scene in which she appears. Humphrey Bogart delivers a compelling and nuanced performance in the film, even when we do not see him. Even his voice work is outstanding. His portrayal of Vincent is a masterclass in film noir acting, showcasing his ability to convey complex emotions and inner conflict.

Bogart’s performance is particularly noteworthy for his use of facial expressions and body language to convey Vincent’s emotions. Even when his face is hidden from view during the first part of the film, Bogart manages to convey a wide range of emotions through his voice and physical presence alone. His expressive eyes, in particular, become a focal point for conveying Vincent’s inner turmoil and determination.

Bogie’s performance is a truly an underrated performance in his illustrious career. With his skillful portrayal of Vincent Parry, Bogart elevates the film beyond its genre trappings, creating a compelling and unforgettable character that lingers in the minds of audiences long after the credits roll.

On an aesthetic level, one of film noir’s most striking elements is the high contrast grayscale imagery. The moody grayscale cinematography brilliantly captures the shadowy streets of San Francisco, thus crafting an atmosphere of dread. Beyond mere aesthetics, however, the lighting and camera movement communicate a sense of unease and mystery, mirroring Vincent’s (and by extension film noir’s) emotional journey through this murky world of crime and deception.

Why isn’t this brilliant picture more well-known? Most likely the reasons are three fold (1) competition from other better-known Bogie-Bacall collaborations like The Big Sleep (2) overt subjective camera framing and movement and (3) availability on broadcast/cable TV and home video.

Points one and three are somewhat interlinked because other Bogie-Bacall pictures like A Gentleman’s Agreement and The Big Sleep are much better known because they received higher praise from critics and audiences (even though Dark Passage received mostly positive reviews at the time of its release). And because of this, other Bogie-Bacall pictures received more airtime on broadcast and cable TV and were more widely available to own on home video and DVD. The second point, which may have led to the mixed-positive reception, concerns the (what would’ve been interpreted at the time as experimental) subjective camera techniques. In retrospect, the POV shots are an outstanding use of motivated camera movement that simultaneously conveys the film’s theme of identity and advances the plot.

While not as well-known as it should be, Dark Passage holds significance within the film noir genre and remains appreciated by cinephiles for its innovative cinematography, compelling performances from Bogie and Bacall, and atmospheric storytelling. And underscoring the technical and performative achievement is the film’s exploration of identity and injustice. It remains a captivating and influential motion picture.

Ryan teaches Film Studies and Screenwriting at the University of Tampa and is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Interested in Ryan making a guest appearance on your podcast or contributing to your website? Send him a DM on Twitter. If you’re ever in Tampa or Orlando, feel free to catch a movie with him.