A darkly comedic commentary on when ambition becomes obsession and obsession begins to rationalize itself as virtue.

There is a fine line between genius and insanity—and How to Make a Killing lives in that narrow corridor where ambition becomes obsession and obsession begins to rationalize itself as virtue. Writer-director John Patton Ford delivers a smart, sophisticated dark comedy that feels as if it has the soul of a 1940s/50s film noir but expresses itself through more contemporary cinematic means. From the moment the movie opens, you are invested in the fascinating confession of the central character of Becket.

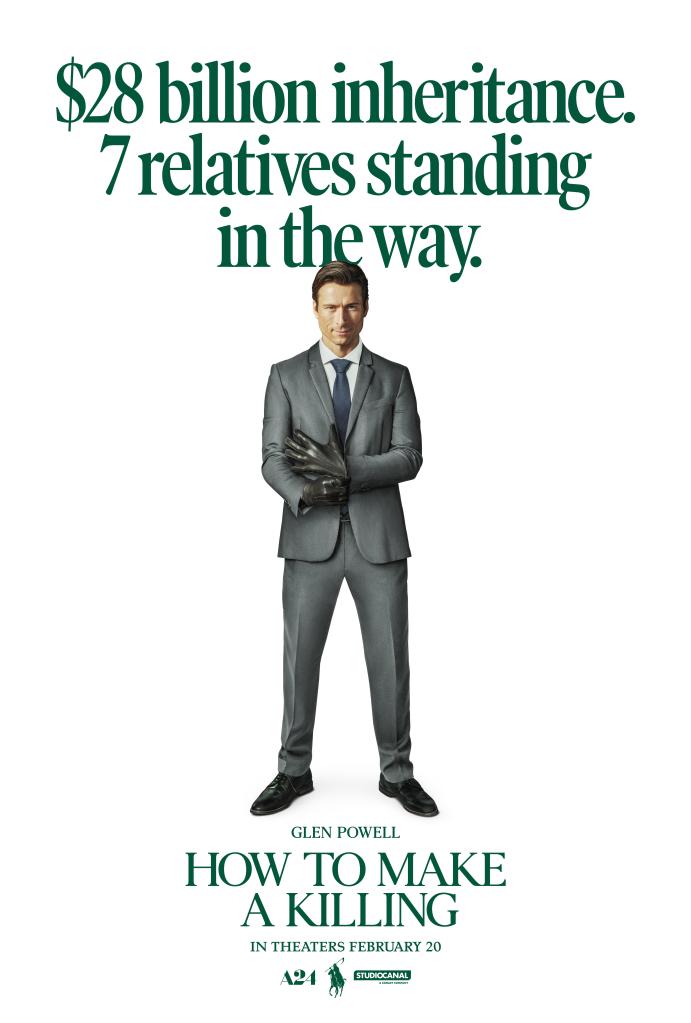

Disowned at birth by his wealthy family, Becket Redfellow (Glen Powell) will stop at nothing to reclaim his inheritance, no matter how many relatives stand in his way.

At its heart, the film reminds us that obsession rarely announces itself as corruption. It presents as vision. As discipline. As genius. Only later do we recognize the erosion of ethics beneath it. Read superficially, the film is a crime drama about financial manipulation and moral compromise. Read more carefully, it is a character study about how the love of money—so often misquoted, so rarely understood—can metastasize into something corrosive. “The love of money is the root of all kinds of evil” is not a condemnation of wealth itself, but of fixation. It is obsession, not currency, that corrupts. And this film understands that distinction with unsettling clarity.

Based upon an early 1900s novel, Ford’s film aligns with and falls within the vein of The Big Short in subject matter but not in spirit. Both explore financial ambition as a moral gamble, but where McKay’s film is kinetic and self-aware—almost gleefully explanatory—How to Make a Killing plays like a contemporary noir stripped of voiceover and venetian blinds. It shares The Big Short’s suspicion of capitalism’s ethical elasticity, yet rejects its comedic distance. Instead, it sinks into fatalism. If McKay’s film feels journalistic—an exposé delivered with sardonic flair—this one feels like a cautionary tale whispered from a holding cell. The satire is muted. The consequences are personal. The system may be flawed, but the focus here is the individual who chooses to exploit it. Tonally, the film feels spiritually aligned with 1940s and 50s film noir. One could easily imagine this plot transposed to postwar America—smoke-filled offices, whispered deals, fatalistic narration. Though not shot as neo-noir, its moral architecture is noir to the core: ambition curdling into self-destruction, intelligence weaponized against itself, inevitability closing in with quiet precision.

Becket is not written as a villain–which is to say that he isn’t written as a classical villain from the outset. But that is the point. He is written as intelligent, disciplined, and—crucially—persuasive to himself. Each unethical decision is internally justified. Each moral line crossed is reframed as strategic necessity. The film traces how obsession reorders one’s moral hierarchy: legality becomes negotiable, relationships transactional, consequences theoretical. It is not greed in caricature form—it is incremental self-deception. Ignoring one’s conscious repeatedly will eventually mitigate the decibel to little more than a whisper before being muted altogether. However, what keeps him from turning completely from sympathetic victim to full-bodied sociopath is that Becket’s conscious does persuade him that there is a line that even he won’t cross.

We, the audience, find ourselves in an uncomfortable position. We root for Becket because we recognize his drive. We admire his focus. We even understand his resentment. Yet we simultaneously want him to stop—to walk away before the inevitable collapse. The film’s framing device, opening where his journey will likely end, casts the entire narrative under the shadow of consequence. It is not a question of whether the fall will come, but how long denial can postpone it and we are held in suspense as to what is going to eventually bring about his downfall. What distinguishes How to Make a Killing from lesser character studies is its restraint. The writer-director demonstrates equal competence in both disciplines—an increasingly rare balance. Nothing feels indulgent. Nothing feels didactic. The film never moralizes overtly; it trusts the narrative arc to indict the behavior. The pacing is clean and deliberate. The plot is simple—but the characters are complex. That is the formula for enduring storytelling.

The film also explores the many faces of wealth—and the different kinds of monstrosity it can produce. There are those who flaunt their prosperity with vulgar bravado, mistaking excess for authority. There are others who manipulate and exploit with a polished smile, weaponizing charm and access as currency. And then there are those who inflate their own sense of importance, confusing proximity to power with moral superiority. Yet the film wisely tempers its critique. Not all wealth is predatory. There are figures of means who genuinely open doors, who extend opportunity—even if their motivations are tinged with ego or paternalism. This nuance prevents the story from collapsing into caricature. The danger, the film suggests, is not wealth itself, but the moral distortion that can accompany its pursuit—or its performance.

Becket’s love interest represents the one thing in his life that isn’t transactional. She falls for him before the money enters the frame—before the inheritance becomes a possibility, before ambition curdles into obsession. He loves her too, in his way. What she offers him is not leverage, not access, not advancement—but something rarer: affection without calculation and companionship without contingency. In another life—or perhaps in another genre—that might have been enough. But noir rarely permits redemption. His compulsion, his fixation on the promise of sudden elevation, becomes the crack in the foundation. The inheritance is not necessity; it is temptation. And temptation, once entertained, demands escalation. The tragic irony is that he already possesses what he claims to be chasing—love, validation, belonging—but he cannot recognize it because he has convinced himself that worth must be quantified. In reaching for more, he loosens his grip on the one relationship capable of saving him. And in true noir fashion, the loss will not feel dramatic when it happens—only inevitable.

There is also a pointed commentary on relationships built upon status, influence, and net worth. The film suggests that when affection is contingent upon achievement—when love materializes only after measurable success—it is less love than leverage. Becket’s romantic entanglement is not merely subplot; it is thematic reinforcement. In the second and third acts especially, he is not simply pursuing someone—he is being pursued by someone whose interest aligns conspicuously with his rising value. That dynamic becomes the first step toward moral descent. Toxic relationships here are not explosive; they are aspirational. And that makes them more insidious. The film quietly warns that those who crave financial or social influence often exploit weakness and tragic flaw, convincing their target that they are both reward and refuge. The toxin may look exquisite—may even taste intoxicating—but it corrodes judgment long before its damage is visible.

How to Make a Killing is not a loud film. It is a steady one. And in tracing the psychology of a man who convinces himself he is justified, it offers a sobering reminder: the most dangerous moral collapses are the ones that make perfect sense to the person committing them–that is, until the pattern is difficult to reverse.

Ryan is the general manager for 90.7 WKGC Public Media and host of the show ReelTalk “where you can join the cinematic conversations frame by frame each week.” Additionally, he is the author of the upcoming film studies book titled Monsters, Madness, and Mayhem: Why People Love Horror. After teaching film studies for over eight years at the University of Tampa, he transitioned from the classroom to public media. He is a member of the Critics Association of Central Florida and Indie Film Critics of America. If you like this article, check out the others and FOLLOW this blog! Follow him on Twitter: RLTerry1 and LetterBoxd: RLTerry